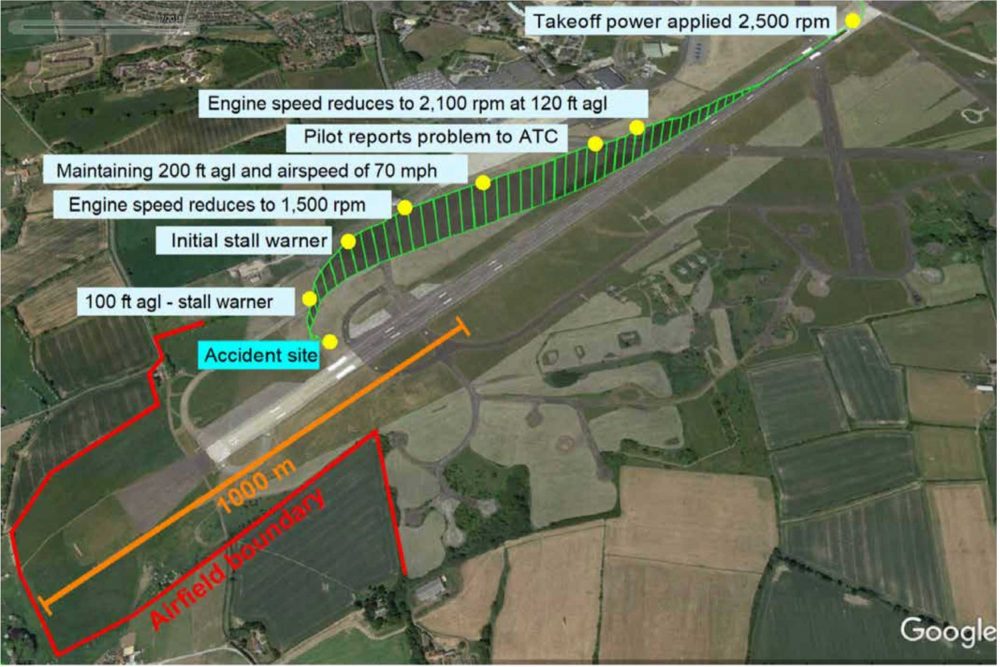

On the morning of 25 September 2021, a Grumman AA-5 took off from Runway 23 at Teeside International Airport. The pilot attempted the so-called ‘impossible turn’ with the unfortunate result of a loss of control and crash, within the airfield boundary, with serious injuries to all three occupants and the destruction of the aircraft.

The pilot was properly licensed, experienced, including more than 800 hours on type and recent.

Much of the CAA report on the accident goes into why the pilot experienced a partial engine failure, none of which was his fault, nor especially relevant to this article.

Suffice it to say that part of the carburettor was found inside number four cylinder and had caused that cylinder to stop working, but that the other three cylinders were doing their best to keep working.

The engine performed normally on preceding flights, during engine checks and the take-off roll, giving normal static rpm, but stuttered to 2,100rpm 14 seconds after take-off, at 120ft agl.

We can be so exact because the rear seat passenger was filming on his phone.

By 170ft, speed had reduced from 70kt to 60kt. This remained the case for only 10 seconds, at which point the aircraft was at 200ft and the engine could only manage 1,500rpm. Airspeed reduced to 56kt and a brief stall warner occurred.

“The engine performed normally on preceding flights and during engine checks but stuttered 14 seconds after take-off, at 120ft agl”

The pilot advised ATC and requested a landing on the reciprocal Runway, 05. The wind was 180/3.

The aircraft had drifted to the right of the runway during all this and the pilot commenced a left turn.

Bank angle increased, as did rate of descent, reaching 1,000 fpm and at 100ft, the stall warner activated continuously until the aircraft struck the ground, five seconds later.

The aircraft had turned approximately 90° and struck the runway alongside the touchdown zone markings for Runway 05, more than 800m short of the airfield boundary on the 23 centreline.

At the time of the partial engine failure, the aircraft had used less than one third of the available take-off run available, and less than one quarter of the emergency distance available, including the grass off the end of 23.

This however, conflicts with the recollection of the pilot, who reported that he suffered the failure at 400ft and decided that the field outside the airfield boundary was full of livestock and people, so had been discounted as an option.

So what caused this discrepancy and what were the pilot’s options? And is the impossible turn impossible?

In a Vy climb attitude, the view over the nose is restricted in most light aircraft. If the immediate action had been to adopt a best glide attitude, the remaining runway would have been apparent and a successful emergency landing probably assured.

The absolute rule is that it is better to land and hit a fence while the aircraft remains under control than it is to lose control and stall in, even from 100ft.

In a partial engine failure, even with 2,100rpm being maintained, a climb is unlikely to be possible. Remember, it is power in excess of that required for level flight that allows a climb.

When a light twin loses an engine, it loses 50% of its power but almost ALL of its power in excess of that required for level flight.

As an example, a Seneca is capable of 1,800 fpm on two engines, but only 180 fpm on one – 50% power loss, but 90% performance loss.

If a light twin loses an engine between rotation and gear up selection, we teach that the immediate action is to close the live throttle and land ahead.

A partial engine failure in a single is much the same. Very few full engine failures after take-off result in fatalities but most partial engine failures after take-off result in fatalities.

Do not overestimate the effect of your remaining power.

The pilot also reported having completed the engine failure checklist. Do not let checklists distract from the priorities.

Get on the ground. Yes, in a skill test, doing the checks in a full engine failure and forced landing is good to see, but getting in the field is the object of the exercise. In an EFATO, not stalling in the startle phase and landing under control is everything. And that impossible turn.

Plenty of US YouTubers seem to have managed it. In STOL aircraft. Remember, a turn back is not a 180. It’s usually a 90+270. At rate 1, that’s a two per minute turn.

You’ll need a 40° angle of bank to make it smartly and that significantly increases stall speed, requiring an increased rate of descent to avoid an accelerated stall.

Having explored all options with another experienced instructor, in a PA28-161, I might attempt to complete a turnback if I had already turned crosswind, so probably at about 700ft or so.

On the climb out, at below 500ft, neither of us could make it back. And we were ready and waiting.

My advice is this. On every take-off, conduct a take-off briefing. Here’s mine, for a single on Cardiff’s Runway 12, which is toward the sea.

“This will be a left seat take-off from Runway 12 with a 5kt crosswind from the left and a 10kt headwind. I shall apply into wind aileron at the start of the take-off roll.

“If I experience any malfunction before rotation, I will close the throttle and stop on the centreline, set the brake then assess the situation before offering to vacate the runway if safe.

“After rotation, if I experience a significant loss of power, I will close the throttle and land on the remaining runway. If there is insufficient runway remaining, I will land alongside the beach, in the water.

“ONLY once safely set up for the emergency landing will I explore options should there be sufficient residual power to offer any, bearing in mind that such residual power may not be relied upon.”

No, I’m not briefing my passengers, I’m briefing myself. I’m preparing for actions best decided upon before they occur, not under stress. Sometimes those options aren’t very palatable, but the worst option is to crash having lost control.

2 comments

Could do with a download option to copy that little bit take off briefing advice. I took a screenshot on my mobile and emailed it to myself. Great article, cheers.

I have always conducted a take off briefing similar to yours, thank to excellent training by Dale Reynolds. I was a share holder in that Grumman and would have been flying it later that day. Definitely made me think more about my briefings.