Out of control

Cessna 210

VH-SJW

Darwin, Northern Territory

Injuries: Minor

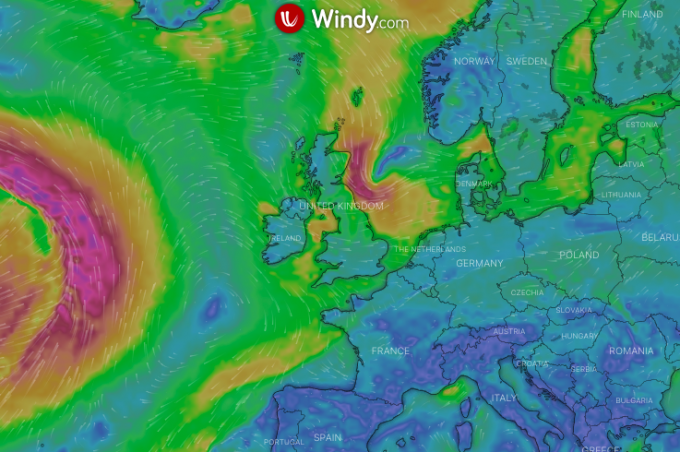

A Cessna 210M was conducting a charter flight with four passengers from Darwin to Tindal. Soon after departure, the pilot diverted 5nm right of the planned track to avoid a large storm cell that was 5nm left of track. About 10 minutes after departure, while maintaining 3,500ft, the aircraft encountered sudden and sustained severe turbulence, the turbulence penetration speed for the Cessna 210M was 119kt.

The pilot stated that, during the incident, airspeed could not be controlled through changing power settings, and for the most part the airspeed could not be held below 155kt. For extended periods, the pilot had no control over bank angle, height, or heading. At one stage, the airspeed dropped below 140kt, and the pilot lowered the landing gear in order to create drag and slow the aircraft down.

“For extended periods, the pilot had no control over bank angle, height, or heading”

The backrest of the centre row of seats could be folded forwards for access to the rear row of seats, which was standard. One centre row passenger found it difficult to brace against the moveable seat back, and although wearing a seatbelt, reported not being sufficiently secure. This passenger’s neck was injured in the incident.

The turbulence encounter lasted about 3.5 minutes. Radar at Darwin recorded the aircraft’s highest groundspeed as 210kt, and rate of descent at one point to be 5,000fpm with a lowest altitude of 1,200ft. Control of the aircraft was lost for more than three minutes, and three passengers sustained minor injuries.

After landing at Tindal and inspecting the aircraft for potential damage, the pilot ferried the aircraft to Milingimbi Island. At Milingimbi Island, the pilot picked up four more passengers for a charter to Galiwin’ku (Elcho Island). The pilot reported the incident to the operator that evening. Upon receiving notification of the turbulence encounter, the operator grounded VH-SJW at Galiwin’ku, pending an engineering inspection.

Comment In this incident, avoiding a storm by more than the recommended separation was not enough to keep the aircraft and its passengers safe. Thankfully, we are unlikely to see storms of this magnitude in the UK, but severe turbulence is not uncommon, so ensuring there are no loose articles and that all the passengers remain strapped in is a must. Inspection of the aircraft ultimately showed no damage but the operator was right to have grounded it, and point out to the pilot that it should not have been flown again following the incident.

Several reasons to fail

Van’s RV-7

ZK-DVS

Te Kopuru, Northland, NZ

Injuries: Two fatal

Seventeen minutes after departing Whangarei aerodrome, a Van’s RV-7, entered a high angle of bank (AoB) manoeuvre, achieving 70°.

Five seconds later, the AoB increased to 130° and the aircraft began to pitch nose-down. During the resulting descent, the indicated airspeed was recorded at 244kt.

Approximately 30 seconds after entering the high AoB manoeuvre, witnesses observed the aircraft break-up in flight and then impact terrain.

The pilot was appropriately rated and current on the aircraft, having conducted approximately 105 hours on type and approximately 20 hours in the last 90 days.

He had conducted his last Biennial Flight Review (BFR) and the instructor stated that he identified no issues with the way the pilot flew. The BFR was conducted in the accident aeroplane. Both medium and steep turn manoeuvres were conducted, and the pilot was assessed competent in both.

According to the NZ CAA Flight Instructor Guide a steep turn involving an AoB of about 60° is generally approved as a semi-aerobatic manoeuvre in most light training aeroplane’s flight manuals.

The pilot did not hold an aerobatic rating and witness statements indicated that the pilot did not like to conduct aerobatics.

Witnesses also stated that he was generally a ‘straight and level’ pilot and would ‘climb to seek smoother air’.

At the time of the accident the pilot had accrued approximately 380 hours fixed-wing experience and approximately 4,300 hours helicopter experience. He held an ATPL-H with an instrument rating and was employed as a helicopter pilot, most recently on a Sikorsky S-76C.

Anecdotal evidence from individuals who knew the pilot, indicated that the pilot liked to fly ‘around the clouds’.

On the day before the accident flight, the pilot had conducted a local flight in ZK-DVS, to the north-west of Whangarei. During this flight, the pilot climbed the aircraft to an altitude of approximately 6,000ft.

On the accident flight the pilot climbed the aircraft to an altitude of about 4,500ft. On both days cloud layers were reported to be either at or below these altitudes.

Comment The report is inconclusive in identifying the underlying cause of this accident, but we do know that an experienced aviator with almost 5,000 hours pilot time, familiar with the aircraft type and more current than many of us, lost control of his aeroplane at height on what was apparently a nice weather flying day.

Although, the combination of a reasonably high performance aeroplane, cloud and startlement would have played a part in his disorientation and failure to take appropriate recovery action.

A good reason, perhaps, to explore the edges of a flight envelope with a qualified instructor as part of some ‘Upset Prevention and Recovery Training’.

Too close for comfort

Fuji FA-200-180 Aero Subaru: G-HAMI

Cessna 172R Skyhawk: G-BXGV

Near Henley-on-Thames, Oxfordshire

Injuries: Nil

Two aircraft had, what was initially believed to be, a near miss while giving air experience flights to disabled children at a multi-aircraft charity event.

It was later discovered that the two aircraft had collided, with one sustaining minor damage, but both aircraft landed safely.

“It was later discovered that the two aircraft had collided, with one sustaining minor damage”

The investigation discovered that one of the accident pilots was asked to present the pilots’ briefing at short notice. The briefing did not include a discussion of how all the participating aircraft would be deconflicted or how they would communicate. It was also reported that not all the pilots that flew were at the briefing.

Both accident pilots stated that their transponders were serviceable, and they were squawking code 7000. However, secondary radar returns were not recorded from either aircraft. It is possible the pilots forgot to select their transponders on. Neither aircraft had any form of EC. Had both transponders been working correctly and one aircraft had EC, the collision might have been avoided.

Recordings of secondary radar might also have given the investigation a better understanding of the circumstances of the collision.

G-BXGV’s pilot was using an electronic navigation aid. Its flight log was made available to the investigation. G-HAMI’s pilot was not using an electronic navigation aid.

The airfield has now installed

a programme on a personal computer in its operations room that enables staff to see ADS-B

and Modes S equipped aircraft, providing a general overview of the local flying area.

Since this system was installed it has been noted that a ‘surprising number’ of aircraft, which are known to have Mode S transponders do not have them turned on, and that this may be because pilots fear the consequences of being observed infringing the surrounding airspace.

Comment For every collision there are numerous ‘near misses’, many of which go unreported and probably many more where neither pilot sees the other. While trusting in luck may be OK for some, a mid-air is not something any of us would want out of choice.

While turning a transponder off may act like the ultimate cloaking device by making you less visible to air traffic, it doesn’t make you any less likely to being hit. Quite the reverse! These pilots were about as lucky as can be, returning themselves and their charges safely back to Earth.

Surviving a midair in which others lose their life would be tough enough, but knowing that one party or the other hadn’t played their part in making themselves visible electronically would be especially difficult to comprehend.