Earlier is easier

Pegasus Quasar IITC

G-MYJT

Brindle, Lancashire

Injuries: Minor

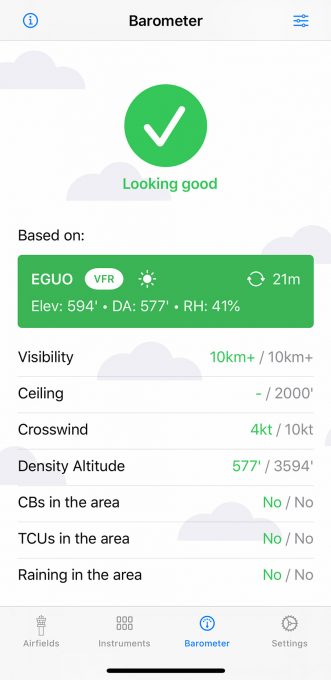

The pilot departed Kenyon Hall Farm Airstrip at 1730 and arrived at Rossall Field Airfield at 1800. The conditions were hazy, but he could see the ground and was able to navigate using a chart.

After a brief visit, he departed shortly before 1900, although he could not recall the exact time. Sunset was at 1859.

During the return flight the pilot reported that the haze was worse, and he realised he was significantly off track to the east. He turned west towards Winter Hill, which was one significant feature on the landscape which was still visible. He reported that as he flew over the hill, the ground was covered in a carpet of haze that obscured most of the features on the ground. He tried, unsuccessfully, to find the track back to Kenyon Hall Farm. He attempted to descend below the haze, but it seemed to extend to the ground with visibility ranging from several hundred metres up to about 4km. The light levels were also reducing.

The aircraft did not have a radio capable of contacting anyone for help.

Flying low, he then passed a radio mast he hadn’t seen and panicked. He decided his only option was to land in a field, but he struggled to pick one due to his emotional state. Eventually, he choose one, but due to the low light levels he did not see the power lines across the approach. According to the electricity provider the aircraft struck the power lines at 1950, and was destroyed when it struck the ground.

The pilot was injured, but he was able to escape the aircraft. He departed with little contingency time before nightfall.

There was nothing in the weather forecast to cause concern. However, his experience on the outbound flight was an indication that navigation might prove difficult on the return flight. The pilot had the option to change his plans and postpone the return flight, but decided to continue. He could not recall his exact departure time from Rossall Field. He may not have realised how long he had spent there or forseen the impact of the weather on his ability to navigate, plus the light conditions. He expected that the return journey would take about 30 minutes, similar to the outbound flight.

If the flight had gone to plan he would have landed at Kenyon Hall Farm before the end of civil twilight.

The navigational problems delayed him to the point where it was dark. Under the circumstances, he had no safe option remaining and decided to perform an emergency landing rather than continue. It is likely that this decision gave him the greatest chance of avoiding an accident, but he was unable to see the power lines and could not prevent the collision.

AAIB Conclusion The accident occurred because the pilot departed too late in the day and was delayed by navigational difficulty until it was dark. He decided to perform an emergency landing, but it was too dark to see and to avoid power lines on the approach to his chosen field.

Comment Even when it looks as if you’ll just make it, often it’s best to just stop early, accepting the fact that things rarely go to plan. In this case, it would have been a major hassle, but better than pressing on until the options remaining were poor.

Details that matter

Beech 36

N5836B

Lubbock, Texas, USA

Injuries: None

The pilot reported that during the take-off roll – and while the aeroplane was about 60kt – it lifted off in a nose-high attitude, and the stall warning horn started up. He added that about 20ft above ground level the aircraft rotated to the right, but he overcorrected, and the left wingtip struck the runway.

Shortly after, he landed the aircraft without further incident. The aircraft sustained substantial damage to the left wing. The pilot reported that post-accident examination of the aeroplane revealed that the elevator trim was set to nose-high and that he should have used a ‘before take-off’ checklist to verify that the elevator trim was set to the ‘take-off’ position.

NTSB Probable cause The pilot’s improper pitch trim setting during take-off in a left quartering tailwind, resulted in the aeroplane abruptly pitching up and subsequently experiencing an aerodynamic stall.

Contributing to the accident was the pilot’s failure to follow a pre-flight checklist and verify that the elevator trim tab was in the take-off position.

Comment Of all the secondary flight controls, pitch trim is in many ways the most powerful. It is key to flying the aeroplane well, but can overpower you in a few moments if set incorrectly.

However, it usually provides warning in the form of abnormal control pressures pretty early in a take-off roll where an aborted take-off is still easily managed.

No house for a mouse

Piper PA28

N68DW

New Market, Virginia, USA

Injuries: None

The private pilot stated that shortly after take-off for the cross-country, personal flight, the engine suddenly lost partial power. Subsequently, he made a forced landing on a cornfield, during which the left main landing gear penetrated the left wing and separated from the aeroplane, the nose landing gear collapsed, and the firewall and engine mount sustained substantial damage.

Post-accident examination of the engine did not reveal evidence of any pre-accident mechanical malfunctions nor failures that would have precluded normal operation. The carburettor exhibited no external damage. However, when the air box and alternate air control were removed, a dead mouse fell out of the intake manifold.

NTSB Probable Cause A loss of engine power on take-off due to restricted airflow to the engine.

Comment This is definitely something to consider as we take to the skies in aeroplanes that have been unused and locked down for long periods of time.

Look before you reach

Robinson R44

G-LLIZ

Sherburn-in-Elmet Airfield, Yorkshire

Injuries: Serious

The pilot arrived at the airfield to complete a solo circuits flight as part of his PPL training. He was briefed by the supervising instructor, and having completed the external and internal checks on G-LLIZ, he started the engine. While it was warming, post-start up, the pilot removed his jacket and put it on the left seat of the helicopter, securing it with the seat belt. He also decided to open both the side vents and the nose vent as the carbon monoxide light had illuminated. This is not unusual when the helicopter engine was running for a period of time when stationary. Opening the vents increased the air movement in the cockpit and the light extinguished.

Having completed the checks before take-off, the pilot lifted into the hover and proceeded to the centre of the airfield to depart for his first circuit.

After landing off the third circuit the pilot realised that his jacket had moved and was now resting next to the open vent in the front left door. He was aware of the risks of items striking the tail rotor when sucked out through the open vent in flight, so before starting his fourth circuit he reached for his jacket.

Although the pilot does not recall the exact sequence of events, it is likely that the jacket was caught around the left collective lever. As he pulled the jacket, it raised the lever, which increased the pitch on the blades and caused the helicopter to pitch nose up. This increase in pitch caused the rear tail stinger to contact the ground. It then yawed to the left before rolling right, coming to rest on its right side.

It is possible that as he reached across the cockpit his body position caused an inadvertent application of left pedal, which also caused the helicopter to yaw.

As the helicopter was in contact with the ground, this yaw caused the skids to catch on the surface, generating a right roll from which there was ground contact.

The pilot was looking inside the helicopter when the movement began, and he had little chance to notice and stop the movement until it was too late for recovery. Only lowering the collective rapidly could have prevented the roll, once the helicopter had begun to pivot about its skids.

Although there are friction devices fitted to the cyclic and collective controls, the pilot did not apply them as he was in the middle of a flight and was planning to take-off shortly after getting his jacket.

It is possible that the application of the friction devices might have prevented the left collective being pulled up by the jacket.

Pilots should always consider the use of the friction devices should they need to move around in the cockpit for any reason when on the ground.

AAIB Conclusion An innocuous reach out to retrieve a jacket that had moved began a sequence of events that led to the helicopter coming to rest on its right side, damaged beyond economic repair.

Whenever a helicopter is stationary on the ground, with the pilot attending to items inside the cockpit, things can rapidly occur that lead to an incident or accident without the pilot being alerted because they may not be looking outside the cockpit.

The whole accident sequence of G-LLIZ took just four seconds. Ensuring all items inside the cockpit are secure, and that the pilot and any passengers are comfortable is vital in order to minimise the risk of such an event occurring.

Comment Aeroplane or helicopter, we tend to let our guard down when on the ground. In many ways, the margins

are slimmer on the ground, and once

the engine is started we need to be every bit as ready to respond as we are when

in flight.