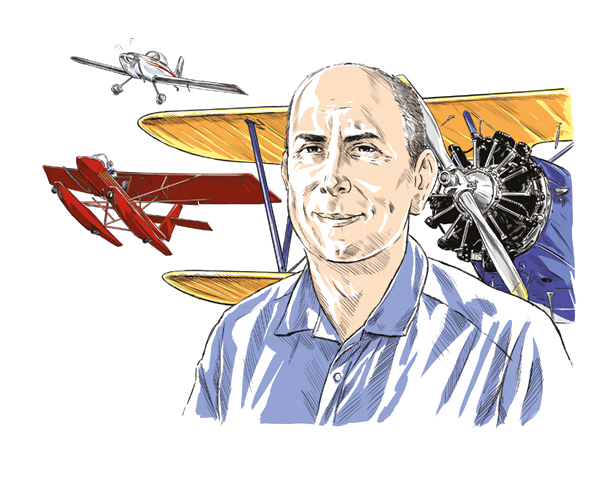

My sporty Van’s Aircraft RV-4 is an ideal commuter for corporate flying assignments – but when I get to the bigger aeroplanes I’ve got to remember to fly differently.

Passengers on corporate jets don’t always appreciate crisp handling and maximum performance the way sport pilots do. Before a recent take-off in a moderately loaded Cessna Citation, for example, I briefed our passengers to expect a sudden burst of initial acceleration. Due to a relatively short runway, I planned to hold the brakes, run the engines up to full power, then release them all at once and gain flying speed as quickly as possible.

If, for some reason, we had to abort the take-off, the technique would provide as much runway surface remaining as possible to bring the aircraft to a stop. Such ‘static’ take-offs are standard for short runways, but they feel much different to passengers than ‘rolling’ take-offs on long runways.

The passengers understood – they seemed to look forward to the energetic departure – and the Citation didn’t disappoint. The departure airport was just a few feet above sea level, and a brisk winter day with dense air meant the jet leapt forward like a sprinter out of the blocks and reached its 100+ knot rotation speed near midfield on the 3,500ft strip. Once airborne, I retracted the landing gear and flaps, while pitching the nose about 17° above the horizon.

I engaged the autopilot and programmed it to maintain 200kt during our initial climb to 7,000ft, and we clawed our way skyward at about 4,000fpm. It was an aggressive climb rate and angle, and it would get the aircraft out of the low-level bumps and into smooth air quickly.

However, my fellow pilot, a corporate aircraft veteran with decades of experience, wasn’t amused.

“It wasn’t my aircraft, so I should fly with a tad less exuberance…”

“Fly the table,” he said. “Why don’t you lower the nose to no more than 10° so that you don’t send our passengers floating at zero Gs when we level off?”

He had a point, and I took it to heart. This wasn’t my personal aeroplane, so I should fly with a tad less exuberance. The static take-off was the right thing to do, along with setting passenger expectations. But there was no need for a steep climb. I adjusted the autopilot that directed the aircraft to fly at a faster airspeed, and the pitch attitude came down to 10° and stayed there for the remainder of our climb to the flight levels.

Lowering the pitch attitude made sense. But what did the other pilot mean when he told me to ‘fly the table’? It was a term that I’d never heard before.

“Think of the table in the cabin,” the more experienced flier said. “Fly in such a way that items placed on the table won’t slide off during the trip and you’re ‘flying table’. Think in those terms and it’s easy to be smooth.”

‘Flying the table’ is the opposite of the crisp, hyper-precise style that aerobatic pilots are taught to fly. When manoeuvring in my own aircraft, I seek out maximum performance. When climbing, I’m as close as I can get to best rate. When flying rolling aerobatic manoeuvres, I use full aileron deflection. When landing, I use full up elevator. It’s an all-or-nothing affair. Jets require a different discipline. It’s extremely rare to bank more than 30° at any time. At high altitude, the maximum rate is 15°. Pilots strive to begin and end climbs with subtlety, and roll in and out of turns slowly.

One of my corporate mentors keeps the yaw damper on, even when the rest of the automation is off, until the aeroplane is less than one mile from the runway. The yaw damper prevents the side-to-side motion from rudder inputs that passengers can find disconcerting – but tailwheel pilots like me use for fine-tuning alignment with the runway centreline.

In other areas, corporate pilots commonly push their aircraft as far as they’re legally allowed. Citations, for example, typically fly at or near their service ceilings at 41,000 to 45,000ft. Doing so keeps them out of the way of faster airliners, lowers fuel consumption, and increases range. When they descend, they typically fly as fast as their aeroplanes allow to 10,000ft, and then they go as fast as they’re legally allowed (250 kias). Few sport or aerobatic pilots spend so much time at or near an aeroplane’s redline, or its service ceiling.

Although the flight disciplines themselves are vastly different, the satisfaction that comes from a well-flown corporate trip is much the same as the joy that follows a well-flown aerobatic sequence. In each case, the pilot has a well-defined goal, and accomplishing it requires performing a series of specific and sometimes demanding tasks in a particular order while avoiding errors. Sometimes, accomplishing the tasks seems quite natural and easy. Other times it’s an endless problem-solving exercise full of odd and unwelcome surprises. But the rewards for a job well done are there on every flight. You just have to remember what aircraft you’re flying.

RV-4 pilot, ATP/CFII, specialising in tailwheel and aerobatic instruction in the USA

[email protected]