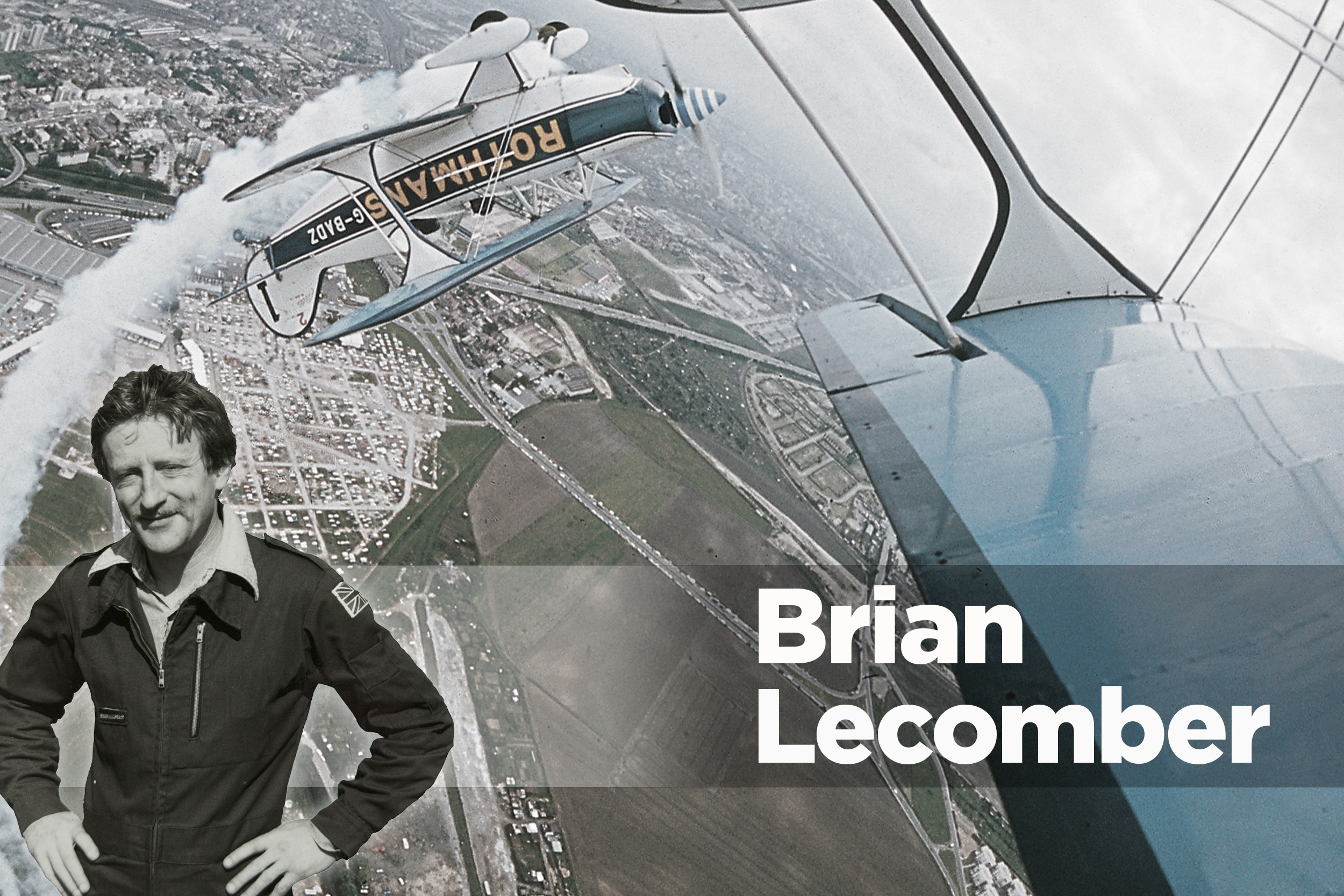

Back in 2013 Brian Lecomber wrote his last column for FLYER. He passed away in September 2015, leaving the world poorer for his absence, but richer for the memories and writing he left behind. Brian spent many years on the circuit as a very accomplished member of the Rothmans aerobatic team, and of his own Firebird Aerobatic team.

In addition to his novels, Brian wrote about motoring and, of course, aviation. We’re reformatting his previous FLYER columns, this appeared in FLYER in Summer 2013.

Pilots come in all shapes and sizes. Fat, thin, male, female, tall, short, bald and hirsute. Their skin may be pasty-white or coal black or any hue in between. They may be at any experience-level from 50-hour PPL to 20,000-hour airline captain.

But – shapes and sizes and colour and creed notwithstanding – ALL pilots also fall into one of two categories. They are either Airman or Aeroplane Driver.

There is a difference between the species.

An ‘airman’ (man or woman) will regard every ascension as at least a small opportunity to acquire a tad more skill in operating these strange machines Mankind has devised to out-fly the birds in their natural element.

An ‘aeroplane driver’ may outwardly look much the same – but the credo is different. To the driver the last flight test / check ride is the Holy Grail, proving their ability to operate an aircraft. There is no need and no desire to go beyond that. I’m there, I’ve cracked it – why go further? Even if there might be a further…

Of course I exaggerate the division. It is not so clear-cut – but it is, nonetheless, there, and very real. And it takes little account of flying hours or experience. Some 50-hour PPLs may be rising airmen – and some 20,000-hour captains may be forever mired in the role of driver and screen-watcher.

How to tell the difference?

There are of course a thousand ways. But in straight-winged GA aircraft there is one small clue most easy of observation. Just watch the pilot make a simple turn. If an airman is flying it, it stays in balance. If the guy in the cockpit is merely an aeroplane driver – then it probably doesn’t.

I’ll tell you what will happen when a mere driver is in the seat. If he / she wants to turn (say) left, then as the bank rolls on the slip-ball will move out to the left. Once the bank is established the ball will move back to more or less the middle. Then, in rolling out of the turn, the ball will slide to the right.

Simple as that. Someone is just driving the aeroplane. Not flying it.

Indeed, you don’t even have to look at the ball. You can see it visually.

As the bank commences, the nose initially carries straight on and only starts to move left when the bank is established and held. Then when rolling out, the nose keeps turning for a second or two, then finally yaws back as the wings come level.

Oh, crude, crude aeroplane driver.

The culprit, of course, is aileron drag. Move the stick left and the left aileron comes up into the low pressure airflow on top of the wing, while the right aileron goes down into the high-pressure flow under the wing.

It does not require a Grand-High-Poobah of aerodynamic science to tell us that the aileron down-going into high pressure airflow will create more drag than the one up-going into low pressure.

Ergo, when rolling into our left turn, the greatest drag is on our right wing, trying to turn us right – exactly what we don’t want. Only when the bank is established and the ailerons are (more or less) neutralised does this asymmetric drag go away (more or less) and the nose start to move round the horizon as the ball slides back to the middle. More or less. Then the same thing happens the other way round when rolling out of the turn. The whole inconvenience is called adverse yaw.

This phenomenon is no sudden revelation – very far from it. The Poobahs have been aware of it for more than a century (in fact since 1868 when an Englishman called Piers Watt Boulton patented the idea of ailerons, exhibiting a fine disregard for the minor detail that at the time there existed no such thing as an aeroplane to bolt them onto).

Since flight began, solutions (or partial solutions) to aileron drag have been many and varied. Differential ailerons, slotted ailerons, Frise ailerons, reflex ailerons, even partially or fully coupled aileron and rudder systems – you name it.

In fact, you can almost plot the course of aeronautical history by the way ailerons behaved over the years. In veteran times aileron drag was what we would now regard as horrendous.

Fly a 1917 Sopwith Camel (certainly one of the best of the WWI fighters), take your feet off the rudder bar, bank left – and the nose will immediately zot off to the right, courtesy of aileron drag. And it will continue to so zot. It won’t come back. The Camel’s natural preferred flight attitude is the steepest side-slip it can rack itself into. Not actually difficult to counteract – but back in 1917 you did have to have educated feet. Which you developed as a matter of course, simply because all aeroplanes of the period did the same thing, most of them with even more gusto than the Camel.

Bring us to the 1930s and the ubiquitous Tiger Moth. The Tiger had massively differential ailerons – the up-coming aileron moving up about seven inches, while the down-going one moved down about an inch and then came back up again to something like half an inch deflection.

So, more drag on the into-turn wing than the out-of-turn wing. That’s aileron drag licked, then…

Except that it wasn’t. Extreme aileron differential is a fairly agricultural solution, but the Tiger was a fairly agricultural aeroplane, so you’d have thought it would have worked. But it didn’t. Oh, the Tiger certainly wasn’t such a crosspatch as the Camel – but it still had adverse yaw stamped all over its forehead. In later years it would become known as a ‘rudder aeroplane’ – not meaning the rudder was a primary control, but meaning it sorta felt like it, and if you couldn’t hack rudder co-ordination in fairly short order you were going to be binned from the course anyway.

Needless to say, young Lecomber found rudder co-ordination difficult. Hell, I found everything difficult except pushing the bloody Tiger back into the hangar. My chief instructor and mentor (known to me privately as Tormentor) was apt to become acerbic about this at times.

“Look, you ride a motorbike. What d’you do when you go round a bend?”

“Well, lay the bike over…”

“Brilliant. How?”

“How? Well… I, er, I don’t know really. You just sort of do it…”

“You just sort of do it. Has it occurred to you that what you’re actually doing is keeping in balance? Keeping the weight of you and the bike going down the centre-line of your body? Well, that’s what you’re supposed to be doing in the bloody aeroplane, too. Can’t you feel when you’re slipping or skidding? Can’t you feel it through the seat of your pants?”

Well, the fact was no, I couldn’t. Not all the time. I have to say, “Yeah, I do feel it, but it’s always a bit too late. I’ve already done it – got out of balance.”

“Well, don’t,” snarls my Tormentor in his best sympathetic instructional manner. “You’ve gotta learn to listen to your ass, boy. Feel through your ass! Develop your ass!”

Oh, thank you, my mentor. I will now commence to have consultations with my own backside and hope nobody sees me doing it.

But he was right. You do have to feel co-ordination through your ass. Or through your ear-balance channels or your hands or your feet – but you do have to feel it…

Only – some of us don’t. Or not intuitively in the beginning, anyway. In the press of other events a small slip-ball error tends to go to the bottom of the to-do pile. Thus heading us towards the pit of becoming an aeroplane driver.