“Grandad had abandoned it out in a cotton field and dad and I pulled it out of the weeds and worked together to get it running. Later we worked on restoring a 1955 Chevrolet. I found I just like bringing old machinery back to life. I see the things that don’t fit – usually stuff that’s been added or subtracted over the years – and I really like the small, intricate systems that were used before the era of throw-away electronics. So I was looking for an aircraft to restore, but not restore too much. My practice was not going to allow me the time it would take to rescue some half-rotted barn find.”

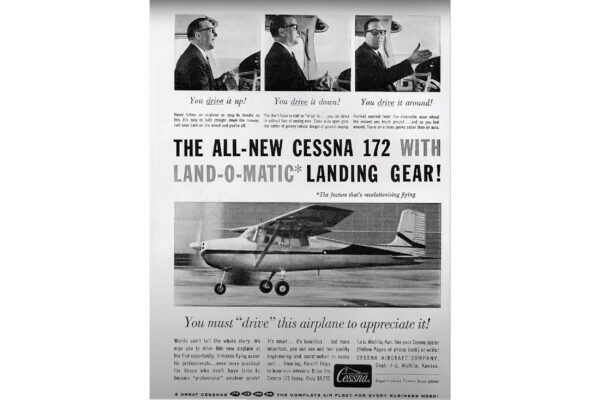

One year later, and still searching, Dennis spotted an ad for a Cessna 172 sitting on a Texan airport. It claimed to be the very first Cessna 172, but the blue and white part job set off Dennis’ alarm bells.

Dennis remembers, “That paint was all wrong, but I called anyway, and Joe Nelson, the owner, set me straight. The aeroplane had been repainted, but it really was the first 172. I was interested enough to take a jet to Texas.” Once there he met his father and together they went over the aeroplane with Joe.

Despite having been in a T-hangar, almost forgotten, for about 20 years, it was in decent shape. Joe had spent a lot of time and energy returning it to airworthy condition, concentrating on the things that it needed so it could fly safely, rather than cosmetics. It was what Dennis had been looking for: a flyable aircraft that could be returned to its original form and had the bonus of historical significance. After talking it over with his dad and thinking about it for a while, he called Joe and made the deal.

The flight home from the Dallas area to Quincy ended up being a test of pilot and machine.