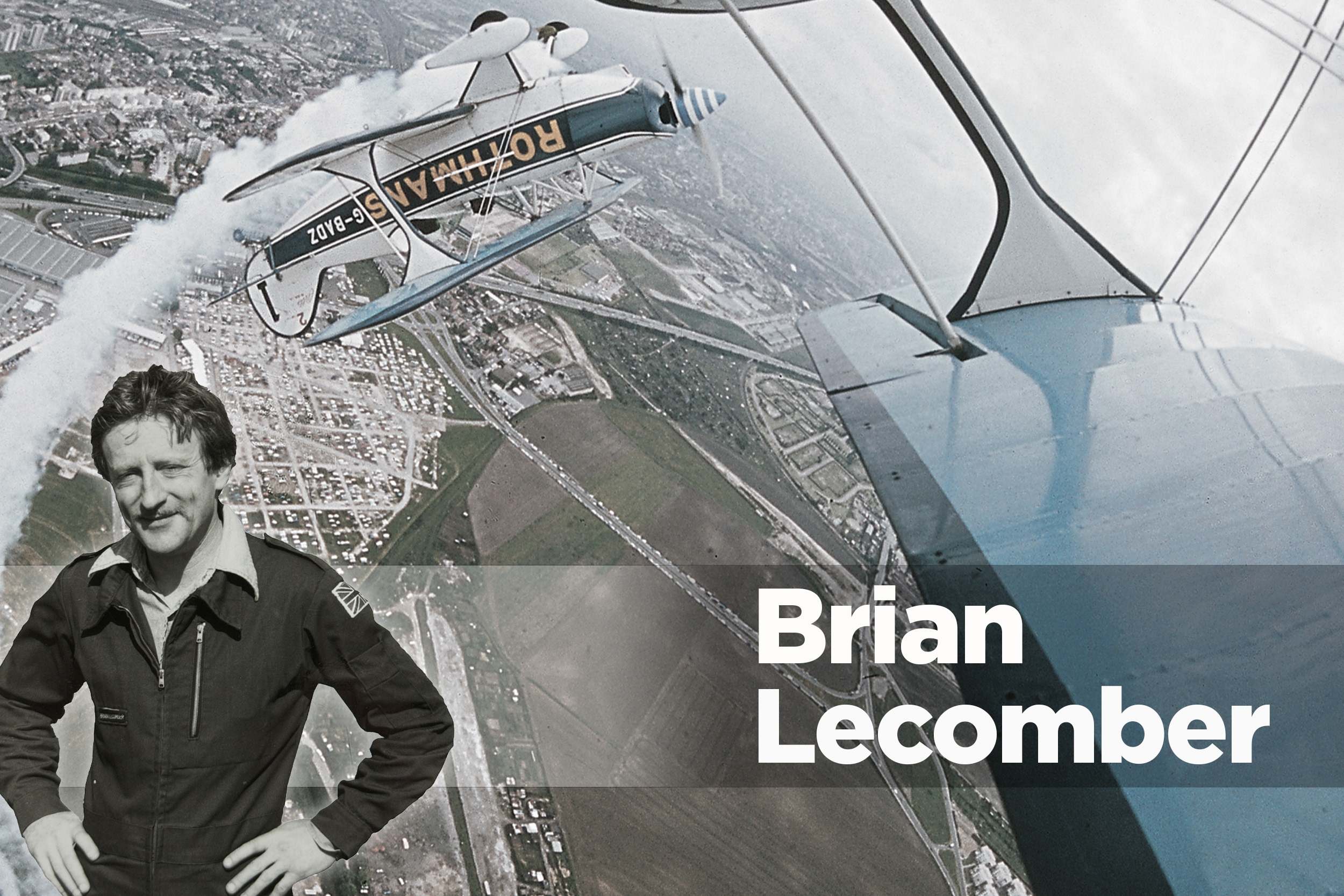

Back in 2013 Brian Lecomber wrote his last column for FLYER. He passed away in September 2015, leaving the world poorer for his absence, but richer for the memories and writing he left behind. Brian spent many years on the circuit as a very accomplished member of the Rothmans aerobatic team, and of his own Firebird Aerobatic team.

In addition to his novels, Brian wrote about motoring and, of course, aviation. We’re reformatting his previous FLYER columns, this appeared in FLYER in July 2013.

The blunt truth is that Peter in the front cockpit has the natural pilotage ability of a hamster.

As check-pilot I had to help him on the rudder as the Chipmunk tried its usual mild swing on take-off. I then had to help him persuade it into a spin and subsequently to recover therefrom. Now I have asked him to slow-roll the aeroplane, with the unappealing result that we have entered a sort of Kamikaze death-dive just after passing through the inverted.

“I have control, Peter.”

“You have.”

On return to our point of origin Peter achieves a bounce of quite awe-inspiring magnitude and then does nothing to rescue it, perhaps expecting it will settle of its own accord. Which it will not, or at least not without the undercarriage sticking up through the wings. I grab control and land.

I am not quite sure what to say to Peter. If he was a new 50-hour PPL I wouldn’t have been surprised by the spin and slow-roll. But if he’d been a 50-hour PPL I wouldn’t have asked him to do them on a first flight in a new type anyway. (Well, certainly not the slow-roll.)

But Peter is not a 50-hour PPL. He is a 4,000-hour airline First Officer, shortly to be promoted to Captain if the star signs continue to smile upon him.

Ahhh…

Do not get me wrong. In my lexicon of almost religious respect there stand a goodly number of airline pilots. In current times and close to home are the likes of Paul Bonhomme, Steve Jones, Tim Barnby, Al Walker, Brian Smith – and a hundred others. On a workaday they will fly a Boeing or Airbus. During their precious time off they may fly Unlimited solo or formation aerobatics. Or a WWII fighter or bomber. Or a very high-performance glider.

These people are the polymaths of aviation – the airmen of all airmen. For what it may be worth coming from me, I salute you.

Peter, however, is not about to join your ranks. Or not any time soon.

For Peter is one of the new generation of airline pilots. About whom, along with legions of older airline pilots, I am deeply worried. Because Peter is, quite frankly, a lousy handling pilot. Or at best, a markedly amateur handling pilot. An amateur pilot with 4,000 hours and coming up for command of an airliner carrying 200-plus blindly trusting homo sapiens…

So as we climb out of the Chipmunk I don’t know quite what to say. I can’t just say, “Now sit up and fly right.” But that’s what I need to say in some form…

I say, “Let’s go and have a pint.”

Halfway through one beer is enough for Peter to open up.

“I flew badly today.”

I rock my hand and take a swig.

“And you’re wondering how to tell me so.”

I can only nod. That is exactly what I have been wondering.

“Well, today was the first time I’ve been in a spin. And the first time I’ve ever been upside-down in an aeroplane. Not to mention the first time I’ve flown…” he grins very faintly… “or failed to fly, a taildragger.”

“Ahhh…” I try to keep my face immobile but inwardly I am staggered. To me this sounds incredible, almost unbelievable. A pilot with 4,000 hours never having spun or rolled? Surely that can’t be possible?

“I know what you’re thinking.” Peter is studying his beer. “I’ve got about 4,000 hours in my logbook as you’ve seen, and I’d guess you’ve got about the same?”

I shrug. This was a long time ago.

“And out of your 4,000 hours, how much was hand-flying? No autopilot?”

I stare at him. “Well, 4,000 hours. All of it. I’ve never flown with an autopilot.”

“How much do you suppose I’ve hand-flown? Take a guess.”

“Hell, I don’t know. Maybe half the time?”

“I wish,” he says. Then, “Look, I’ll tell you. I’m on short-haul, so we generally fly four sectors on a working day – maybe three. We divide the flying 50/50, so the Skipper’s PF – Pilot Flying – for two and I’m Pilot Flying for two. The other pilot’s PNF – Pilot Not Flying. So I fly two sectors – say it averages out at about an hour a sector. What do you think I’m doing in that hour?”

“Well, I guess there’s a lot of button-punching and computer programming…”

“That’s so. But how long do you think I get to hand-fly it?”

Of course, I do not know. This is a different world. I can only look quizzical.

“Well, the average time for any modern airliner flight to have the autopilot off is about six minutes per flight. No matter the length of the flight.”

Sometimes you can only gape. Realising my mouth is open I pour some beer into it. Peter takes a sip.

“Think about it, Brian. I spent about 300 hours on initial training and that was mainly hand-flying. Then I went on the line. Apart from simulator training we get four take-offs and landings a day. Except we don’t – we each only get half of them. Two. On a clear VMC day we click on autopilot passing 1,000ft in the climb, and on descent switch if off again passing maybe 2,000ft. If the weather’s IMC we’ll engage it earlier and leave it on auto to very short finals or even to auto-land, and just monitor it.”

“Jesus…”

“Yeah. So I get to hand-fly maybe 10 minutes a day – 10 minutes when I’ve logged four hours. Beyond training that gives me – about 200 hours actually flying. The rest of the time I’m pushing buttons. And I’m lucky because I’m on short-haul. Think what it’s like on long-haul where there may be four crew and only one landing in a 13-hour flight…”