Pilots can all agree that flying is an amazing experience, but imagine what it’s like to fly an aircraft

that you’ve built, which you’ve personalised exactly how you want it? Thousands of pilots have done just this, and today’s modern kits and equipment make it easier than ever to build your own aircraft.

In the UK, you can build your own aircraft in a number of different ways, but the most popular route is via the Light Aircraft Association (LAA), under the supervision of one of its UK-wide network of inspectors. There are around 200 approved designs you can choose from, though most new builders choose from around 30 of those, as they are the most current, supported types.

Permit Aircraft typically offer some of the best combinations of great handling and performance. There’s even an option for some specific types to be approved for IFR flight too.

Homebuilding is an excellent way to get the aircraft you want, to your personal specification, and to spread the costs over time, if you’re trying to keep to a budget.

Plans or kit?

Only a handful of people build from plans, but it’s probably the cheapest route into homebuilding. There’s machines to cater for all requirements too, but don’t forget, if you plans-build, you’ll be responsible for sourcing all the materials and parts for your project. It’s a mighty task, but well within the realms of an organised builder.

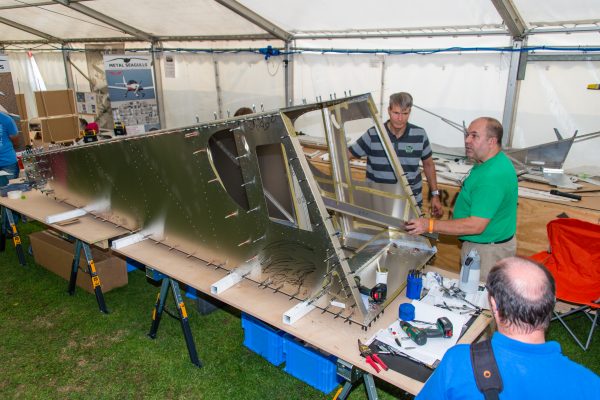

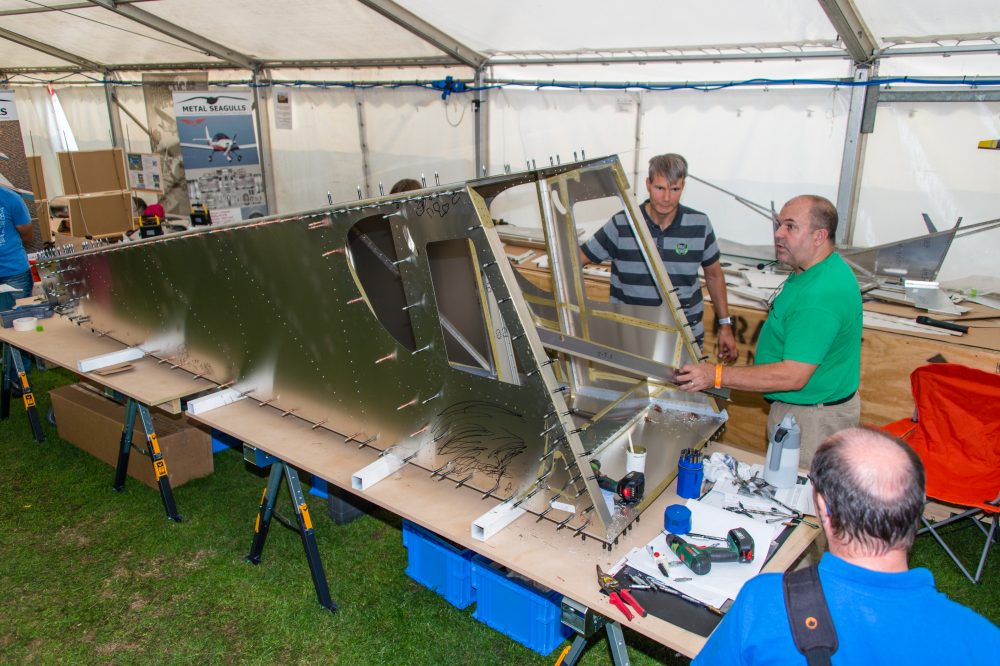

For that reason, most builders opt for a kit aircraft, and today’s modern kits have evolved to be quite advanced in their presentation, with many designs having structures that self-jig if you follow the instructions correctly. There’s three types of kit, and you’ll typically hear them referred to as a ‘flat-pack’, which is the whole airframe supplied in component form. Then there’s the ‘quick-build’, which will see a partially constructed airframe, typically a fuselage tub and partially finished wings, delivered to the builder. Finally, there’s ‘fast-build’, which sees individual sub-assemblies, delivered mostly complete, with the bare minimum to do before inspection and closure of the structure. Some options include pre-covering and pre-painting. Opt for this level of kit, and you’ll ‘just’ find yourself having to complete the instrument panel, install the engine and associated firewall-forward components – and fit the interior trim.