Unfortunately, the airfield at IWM Duxford was closed due to Covid-19 but had agreed to open especially for us on the Wednesday. However, if we stayed in Inverness for the night, that would increase the risk of us getting stuck waiting for a weather window large enough to fly the near 500 miles back from Scotland to Cambridge under VFR conditions. The decision was made to fly as far south as possible on Tuesday afternoon to minimise that weather risk. With limited daylight hours, Tatenhill in the Midlands was chosen, just 100 miles from

IWM Duxford.

The flight south went perfectly. Both engines behaved and the blister window repair held up perfectly. The views throughout the flight were stunning, taking in the Scottish Highlands, Lake District and Peak District en route in the watery winter sunlight.

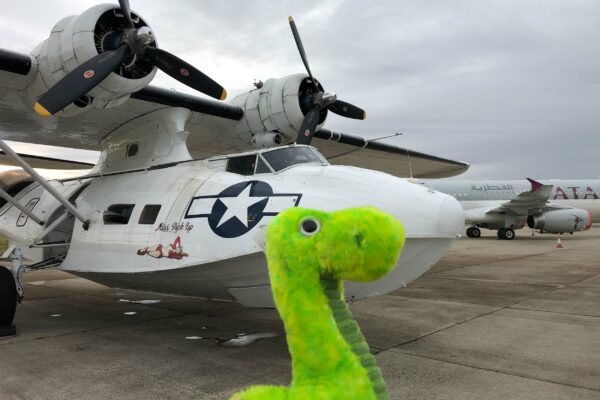

Miss Pick Up touched down some two-and-a-half hours after departing Inverness for her night stop just before sunset. We put her to bed for the night under the stars and hoped the skies didn’t stay too clear as frost would have presented a further problem. Like all aircraft, she cannot fly with ice on her wings.

Thankfully the skies did cloud over enough and kept the frost away. With the en route weather looking suitable and Miss Pick Up raring to go, we took off into the winter skies once more for the final time that year. After another smooth flight, Miss Pick Up touched down in IWM Duxford on Runway 24 at 1148 on Wednesday 2 December, having spent over six weeks stranded at Loch Ness.

Thank you again to everyone who has donated to this rescue mission. We are eternally grateful to you all. Please DO come and see us next year at IWM Duxford where we would be delighted to show you around Miss Pick Up and thank you in person for your generosity.

A lot of people have asked if there will be a documentary about the whole operation and I am pleased to write that yes, there will be! The film crew team from Plane Resurrection followed us throughout the mission, so look out for it during summer 2021 on your TV!