Cross words

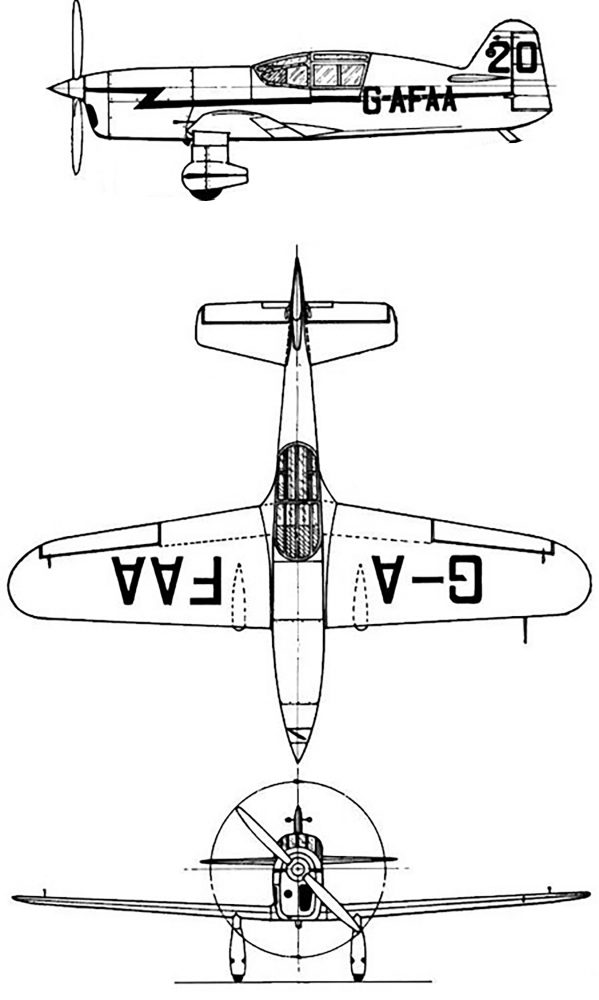

Jack Cross was a well-known air racing mechanic and proprietor of Essex Aero at Gravesend. He was already servicing AEXF and wrote to Henshaw, saying that for the princely sum of £175, he could definitely make the Mew Gull 25mph faster… It’s the kind of offer no racer can ignore and Henshaw agreed. Cross made a number of mechanical and aerodynamic changes, the more obvious ones involving reduction of the canopy’s height to be almost level with the turtle deck and strapping up the undercarriage legs to pull them up and reduce drag. David Beale says Cross did something else on the underbelly but can’t find out exactly what it was, but the results were clear. Henshaw won the 1937 King’s Cup at record speed.

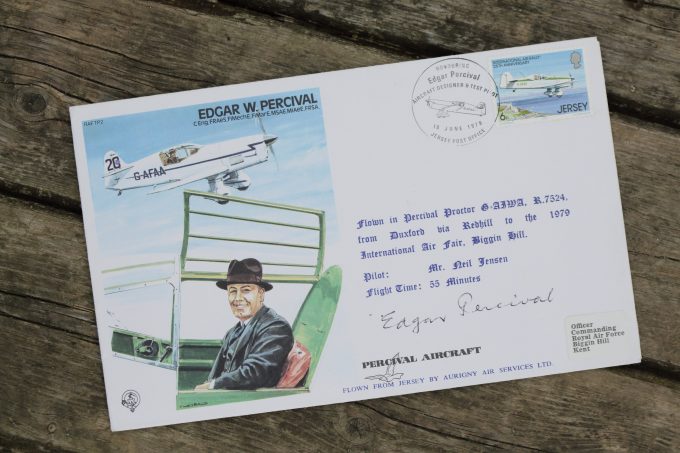

Edgar Percival was distinctly unimpressed despite the success and when Tom Storey and Martin Barraclough completed the first rebuild in the 1980s, Edgar Percival refused to go and see the aeroplane at Old Warden unless Messrs Cross and Henshaw were definitely not present. He had apparently remarked that they had ruined a perfectly good aeroplane, and how dare they call it a Mew Gull… They had taken an aeroplane with almost no forward visibility, and made it worse…

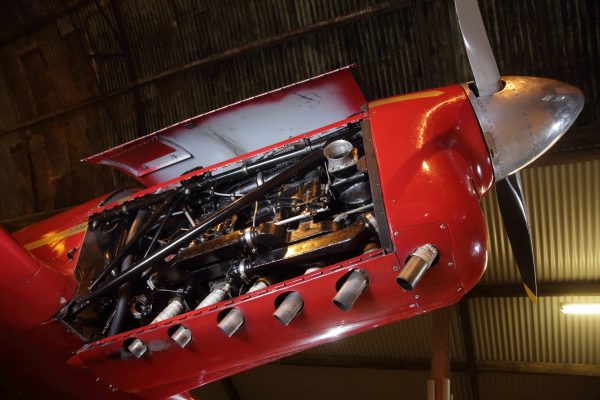

The less obvious change to AEXF was the installation of a very rare and exclusive Gipsy Six ‘type R’ engine, specially produced for racing by de Havilland for the Comets, but with an additional hike in compression ratio by Cross to somewhere around 7:1. Power output was not quoted, but probably somewhere close to 260hp. That plus a French Ratier variable pitch propeller with extremely thin blades which was known to be some 10mph faster than de Havilland’s option – essentially a licence-built hydraulic constant-speed American Hamilton Standard.

The Ratier was about four inches longer, which normally necessitated a very long spinner, but the Cross solution was an extension inside a longer nosebowl to accommodate the de Havilland when it was required by the King’s Cup regulations that mandated British built parts.

Over 70 years later, events appear to prove that Cross was a better salesman than aerodynamicist, and that Cpt Percival was correct in his assessment. Beale’s aeroplane is fitted with a standard 205hp Gipsy, (AEXF has a probable five horsepower advantage), but despite that, whenever they fly in formation, David can draw away at will. The 1938 results also prove the old adage that there ain’t no substitute… Whoever said there ain’t no substitute for horsepower, was also right, as the 1938 results prove, but they also prove that the aeroplane could have been faster if Cross had just fitted the engine and left the rest alone. On the other hand, £175 was a tidy sum at the time… The Cross modifications may not have been aerodynamically effective – David reckons they were even counter, because the canopy profile added some aerodynamic lift, rather like the Gee Bee Racer’s barrel fuselage, or for students of the left field, the aerofoil fuselage shape of Steve Wittman’s Tailwind, and the Sorrell Hiperbipe. I’ve owned one of each and they don’t fly like they look…

AEXF has retained the shorter legs, and the Shuttleworth pilots (who have also flown David’s Mew Gull) say it’s easier to place the aircraft on the ground because the shallower attitude allows it to touch wheels before it stalls in ground effect. HEKL’s taller stance means the aircraft will be more tail down when David tries a three-pointer, which risks a vicious wing drop, or the alternative which is to risk a very long float. The Mew Gull stalls energetically at 90mph, but can only be persuaded to land at 85, which is not a very large window. David favours wheeling it on, which is a technique I now employ with almost everything these days, unless I’m trying to get in somewhere a bit short. Always best to check whether I can get out again, but watching David’s rocket-like departure from North Coates that seemed to be a much lesser Mew Gull concern…