I flew Wasps and Scouts in the military: a conversation with John Beattie

Distinguished display pilot John Beattie, who still flies and instructs on the Wasp, chats to Rachel about the two helicopters

As Ex-Commanding Officer of the Royal Navy Historic Flight, John Beattie needs no introduction. Among his vast aviation experience, he has around 3,000 hours on the Scout and Wasp, with slightly more on the Wasp.

A distinguished display pilot in both the rotary and fixed-wing worlds (he holds the Honourable Company of Air Pilots’ Hanna Trophy in recognition of more than 40 years of display flying), his first air displays, in 1973, were on the Scout while on detachment.

John tells me that he’s never had any trouble from these reliable machines – the only problem tended to be the conditions.

“Flying at sea can be lovely, but the North Atlantic in the middle of winter is not necessarily the nicest place,” he remembers. “You’ve got to wait for the seventh wave for the ship to calm down a bit before you can land on it.”

“The Scout is nicer to fly, but they did different things,” he replies, when I ask which aircraft he prefers. “The Scout was anti-tank or utility – we carried four relatively short-range wire-guided missiles, SS11s, and we were down among the trees, climbing to get over power lines. On exercise we probably wouldn’t come above 200ft.”

“We used the Scout in Northern Ireland a lot for stop and search, too. In the ‘badlands’ down in South Armagh, we’d drop four blokes and they’d stop a car. And resupply – we’d send various supplies to places you couldn’t really get to by road with any safety. We’d have a big net full of stuff.”

“The Scout is faster, nimbler, has less vibration. The Wasp, however, had a bigger missile – an AS12 – with twice the range. We’d go booming across the waves at 50ft and then within 6,000 yards we’d pull up to a couple of hundred feet, loose off the missile, come back down again.”

I ask his thoughts on civilian pilots flying ex-military helicopters. “You’ve got to do 10 hours, because of three accidents that occurred in the 1970s and early 1980s, all of which were down to lack of training. In the military, we had Rolls-Royce training, we did nothing but.

“We’d fly 30 hours a month and it would all be training. A civilian might not fly 30 hours in a year, so there is a different level of application. We were immersed in it, and did every aspect of it – instrument flying, night flying, formation, winching, all that sort of stuff that the civilian wouldn’t do – day VFR only now.”

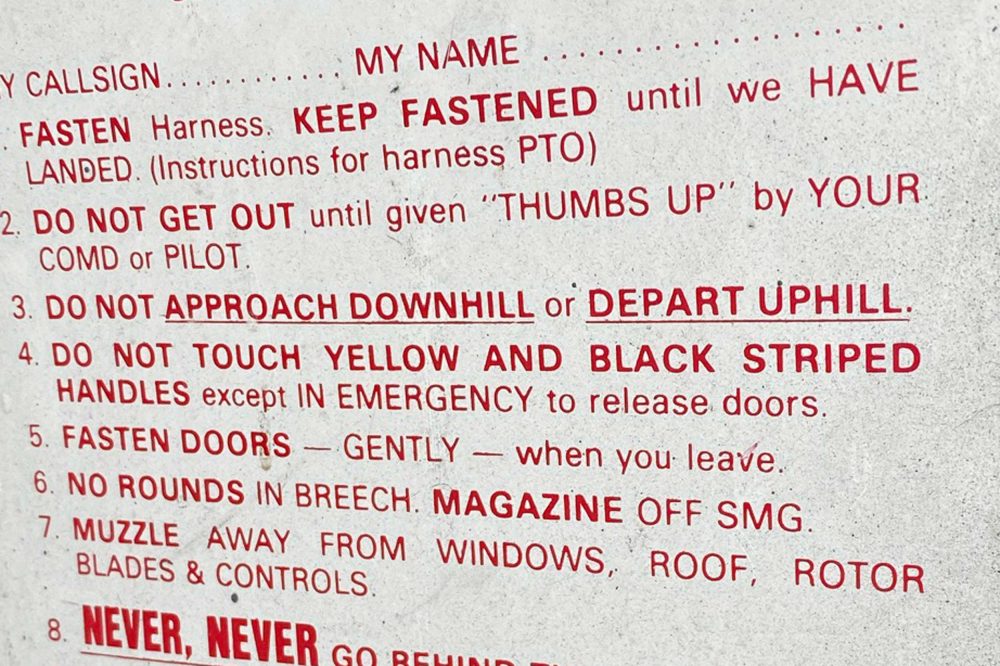

“Civilians tend not to read the pilot’s notes, but we’d sit for hours memorising checklists and limitations. It’s a disciplined background that we were brought up with – if you were in a crew room with 20 blokes all doing the same thing, flying the same aircraft, there’s a lot of cross-pollination and you pick up things from each other. For a civilian on his own, he doesn’t have any of that.”

Nevertheless, John believes that Scouts and Wasps are by no means beyond the realms of civilian private pilots.

“There’s absolutely no reason why they shouldn’t do it,” he replies. “If someone’s got a little bit of cash, the Wasp and the Scout are actually very cheap turbine helicopters. You’ll pay less than £100,000. If you want to fly a JetRanger, you’ll get a 1970s JetRanger for about a quarter of a million – two-and-a-half times the cost.”

1 comment

Great write up…..took me back to post graduate days testing at WHL and more!