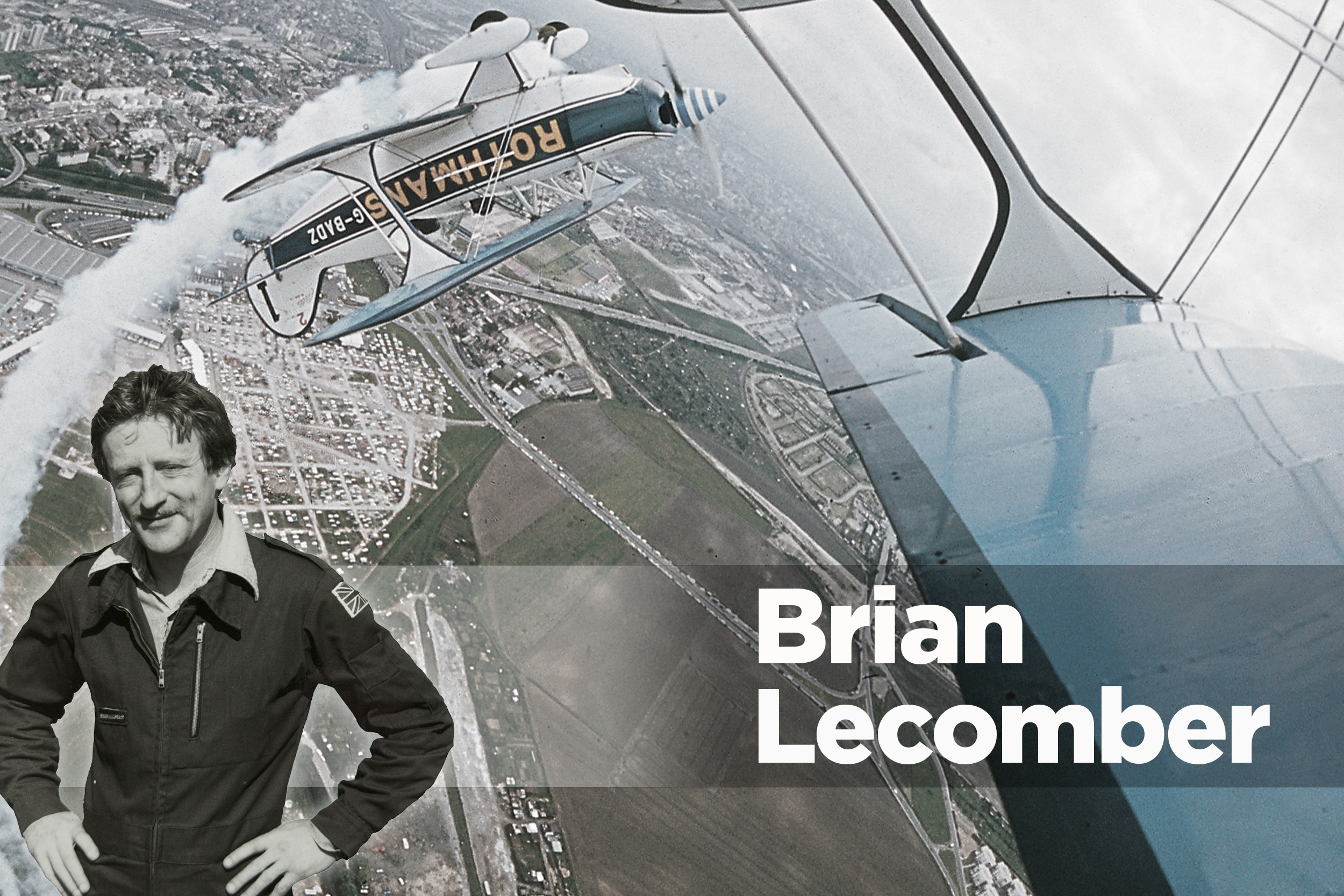

Back in 2013 Brian Lecomber wrote his last column for FLYER. He passed away in September 2015, leaving the world poorer for his absence, but richer for the memories and writing he left behind. Brian spent many years on the circuit as a very accomplished member of the Rothmans aerobatic team, and of his own Firebird Aerobatic team.

In addition to his novels, Brian wrote about motoring and, of course, aviation. We’re reformatting his previous FLYER columns, this appeared in FLYER in November 2013.

It is the year of our Lord 1977. And I am the luckiest pilot in the world. Not, it has to be said, the most comfortable pilot in the world – but certainly the luckiest. The sources of my discomfort are several and purely physical – some trivial, others rather less so. There’s the fact that you can’t see most of the engine instruments without ducking down into the cockpit – and when you do so duck you stand a very good chance of beaning yourself on one or both of the Vickers machine-gun breeches.

These guns – like the whole aeroplane – are not real but extremely accurate full-scale replicas. Replicas which as per the originals protrude into the cockpit like machined-steel anvils and are very capable of inflicting nasty dents in a pilot’s noodle should he momentarily disregard their presence when looking down.

But this is as nothing compared to the main overarching discomfort – which is the cold.

This is an average early-April day – but in this cockpit it is Arctic. Deep mid-winter Arctic during a particularly nippy spell. I have been cold in open cockpits many times before – but nothing like this. It would not surprise me if flying over the British countryside I should suddenly pass over a flag saying WELCOME TO THE NORTH POLE.

Not only does super-freezing airflow seem to rush in from every pore of the fuselage, but the blast around the tiny windscreen – about the size of a letterbox – creates an Absolute Zero cataract which no human bonce was ever designed to withstand.

I resolve to rapidly acquire a burglar’s ski-mask to wear under my helmet so as to bridge the forehead gap between helmet and goggles, which currently feels as if an iced knife is steadily flensing it. (And to think that 60 years ago young men were taking these things up to – allegedly – 20,000ft in mid-winter…).

But ho – I am still the luckiest pilot on the planet. For I am flying a 1917 Sopwith Camel.

Indeed, not just a Sopwith Camel but THE Sopwith Camel – to the best of my knowledge the only airworthy Camel in the whole of Europe at this time. I am following three Tiger Moths and together we are headed westwards towards Land’s End, there to be joined by a Fokker Triplane and other exotic WWI machinery for the purpose of spending a whole week working-up a WWI ‘combat’ display scenario, which will astound the airshow world.

Leisure Sport Ltd, (which are, would you believe, a subsidiary of Readymix Concrete) own the whole shebang and is not mean about its endeavours. Rumour has it that we will be housed in five-star luxury and have absolute freedom to cavort over Land’s End airfield as much as we like. My mind may now be so glaciated that I can’t be bothered to look at a map so just follow the Tigers – but I’m flying a Camel!

And I am already an experienced pilot of the Sopwith Camel. Oh, yes. I have now flown it twice. The first time was about 10 days ago – a flight which lasted a whole 10 minutes and terminated in me scurrying back to the aerodrome with rapidly falling oil pressure. Even at the time I felt this was a tad unfair, particularly as this Camel, in the interests of practicality, is most deliberately powered by a Warner Super Scarab radial engine rather than the original Clerget Rotary.

The Scarab has a life of (if I remember rightly) some 600 hours, while a Clerget (if you can find one) has such a miniscule Time Between Overhauls (TBO) that a transit down to Land’s End, a week’s practice and then transit back would use up almost all of its 25hr engine life. Didn’t matter in 1917. Matters big-time in 1977.

So this is my second flight. I cannot say the aeroplane feels particularly lovely to fly – but never mind that. I now have nearly a whole 30 minutes in it in total…

I duck down to look at the gauges. Just in time to see the oil pressure needle finally settle on zero.

S**t! F**k! B*ll*cks! And all those other calm and professional things you think when the hot flush of fear swamps through your body.

Cold? Suddenly not cold any more. In fact, suddenly quite warm. Action?

This is always the way of an engine emergency. Never mind what the checklists and the training-by-rote say – when it happens for real your first reaction is always disbelief followed by the ‘s**t, f**k’ routine. How many seconds this wastes is probably recorded by some Archangel and affects your overall score when the time comes to either open the Pearly Gates or switch on the electric fence.

Action? Call the Tiger Moths ahead? Impossible. The Camel (surprisingly) actually has a radio, but (unsurprisingly in the ‘70s) the transmit doesn’t work. Also, there is exactly nothing they can do to help me anyway.

The fields nearby are either hilly or small or both. I decide the terrain to the north looks flatter. This is admittedly guesswork, but on the grounds that you have to do something I turn north.

Another guess is how long should I keep this engine running without oil pressure? In a ‘normal’ forced landing your first concern is preserving your little pink body – period. The aeroplane don’t matter.

But this is not a ‘normal’ forced landing. In the clarity of this emergency I find myself thinking that this aeroplane does matter. Write the Scarab engine off – not a huge problem. Damage the Sopwith Camel’s airframe and the only honourable option is hara-kiri as soon as the wreckage comes to rest.

But – there! There – just to the right of the nose. Isn’t that an aerodrome…?

It is. I have no idea what aerodrome and no way of talking to it if I did know – but I don’t care. Whoever it is, they are about to receive an expiring Sopwith Camel whether they like it or not…

The aerodrome is now about three miles away – say two minutes flying. Will the Scarab last two minutes – less for the final glide? I don’t know.

It lasts.

In fact, it runs on seemingly unperturbed. I close the throttle about a mile out. The joint has three hard runways – and needless to say, not one of them pointing into wind. S**t again. The Camel has no brakes and a non-steerable tailskid, and two things have been drummed into me – avoid hard surfaces like the plague, and ANY crosswinds like the Black Death.

My second landing in the device – and with no chance of a go-around – does not seem quite the moment to be trying conclusions with both these strictures at once, so I aim at the triangle of grass between the runways. Of course I don’t know what the surface will be like, but at least it’s a decision…

As I glide past the Control Tower a red Verey flare soars across my nose. Seems they don’t want to receive an expiring Camel, then…

I put the Camel down on the grass, knock the mag switches off as soon as we touch, and sit there waiting for a wheel to drop into a rabbit hole or a comms ditch.