One of the great names of light aviation, Pierre Robin, has died, aged 93. His name lives on with Robin Aircraft which continues to manufacture aeroplanes at Darois, near Dijon, France.

Robin’s best known aircraft is the DR400. More than 3,000 have been produced and most airfields and flying clubs in France will have at least one on the fleet. It’s still in production as the DR401, with the same airframe, enlarged cockpit and electronic flight displays.

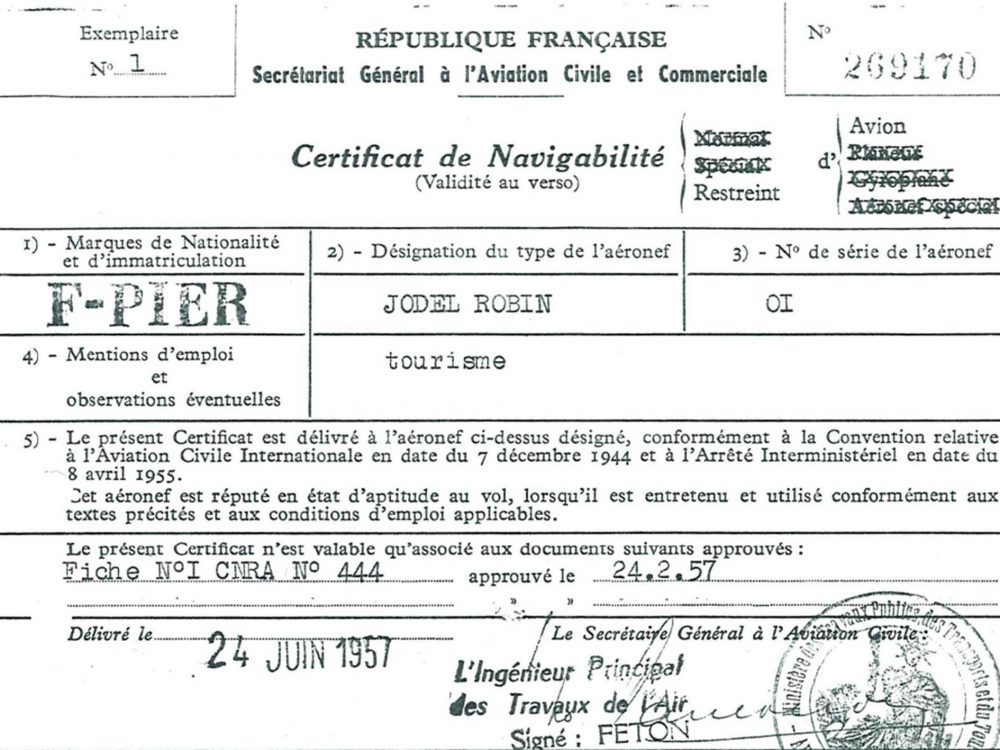

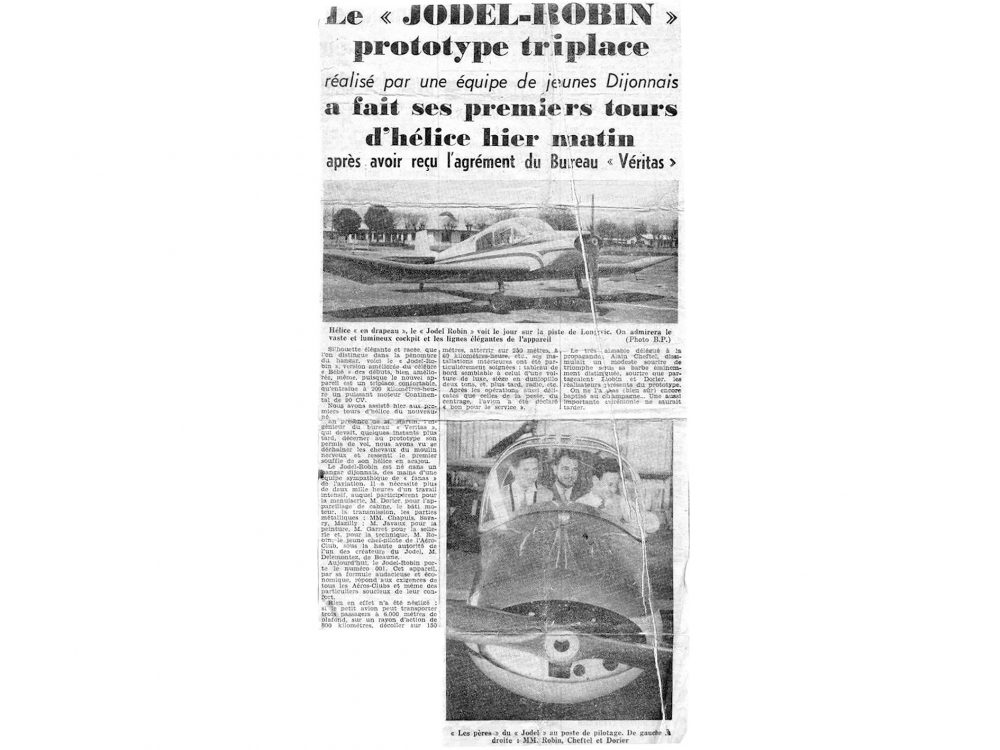

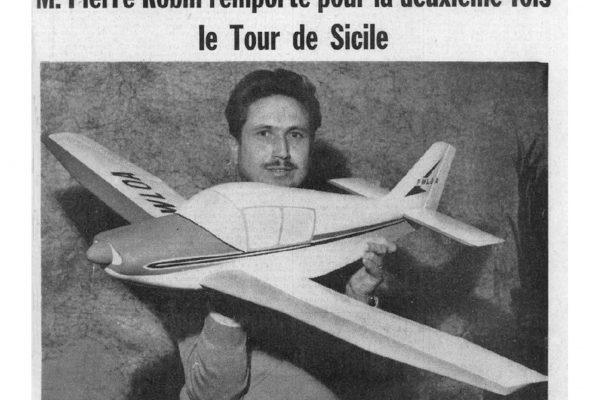

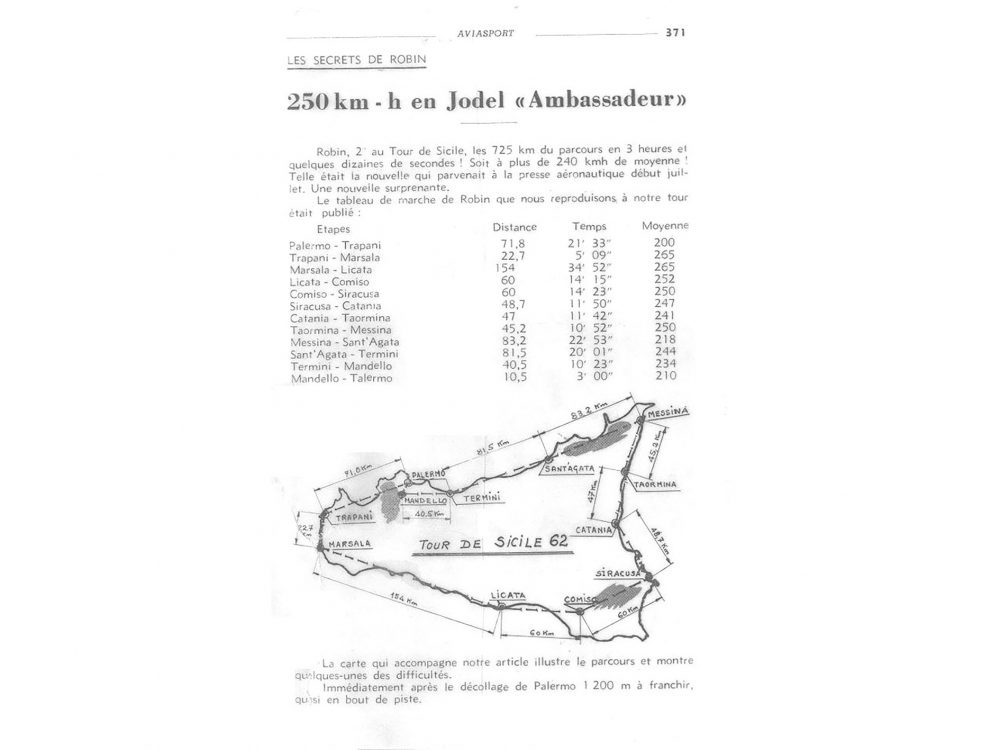

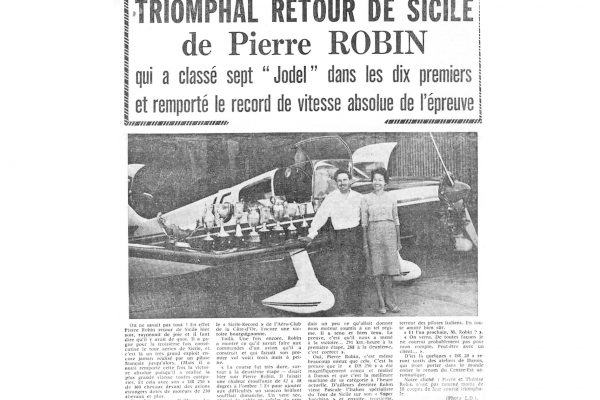

Avions Pierre Robin was founded in 1957 as Centre-Est Aéronautique by Pierre Robin working with Jean Délémontez, one of the founders of Jodel aircraft. Robin’s first aircraft were based on a Jodel design. Later, he produced a metal aircraft, the two-seat HR-200, working with Chris Heintz of Zenair.

Guy Pellissier, part of the management at modern day Robin Aircraft, paid this tribute: “Pierre Robin was an outstanding flying entrepreneur. Jean Délémontez was an outstanding aeronautical engineer. We miss them both and it is a true privilege to extend their legacy.”

Philippe de Segovia, now a director at Daher-TBM, was an editor at Aviation magazine in France in the 1980s, meeting him for the first time in 1984.

“Pierre Robin didn’t speak much, but when he did he had some witty remarks with tongue-in-cheek humour, styling himself as the country farmer,” said Philippe.