Aviation life-jackets are readily available, and at reasonable prices – they are usually very good but with a little effort they can be made even better.

Firstly, just to check: Your life-jackets aren’t self-inflating ones bought from a yacht chandler, are they? If so, can I suggest that you no longer wear them in an aircraft until the self-inflation mechanism has been removed.

The reason being that there have been several tragedies over the years of people being trapped in the cockpit because the jackets have automatically inflated after water entry, leaving those people either stuck like a cork in a bottle, or unable to swim to escape a flooded aircraft due to the buoyancy.

This is the same reason why airline cabin crew tell you: “Do not inflate your jacket until you are clear of the aircraft.” Don’t forget that a high-wing aircraft, for example, will put the cabin under water even if it doesn’t flip on ditching (which despite intuition, often does not happen).

If this is you, then the good news is that many unsuitable self-inflating life-jackets can be modified to manual inflation simply by removing the auto-inflation device, which is usually found by the gas cylinder, so do check that if you have one – and you can fix the problem without spending any money.

OK, that’s that out of the way – now onto the enhancements.

A useful first modification, if your jacket doesn’t already come with one, is to add a spray hood. These are simply transparent face protection visors which covers the head and protect against rough seas, of which splashing waves in the face can results in a build-up of water ingestion into the lungs by the casualty, irritating the lung lining and leading to a fluid build-up (pulmonary oedema).

This can impact the casualty even hours after rescue from the water and is sometimes called ‘secondary drowning’. Retrofit splash hoods cost £20-£40, which may seem a lot for what they are, but are, nevertheless, a good investment. If possible, attach them to the life-jacket as a standard accessory.

Most life-jackets come with a small light as standard, powered by a sea water-activated battery. These are pretty dim, and seem intended more for individual survivors to find each other close by at night rather than for SAR – so you might consider adding a much brighter LED strobe as well to help searchers find you.

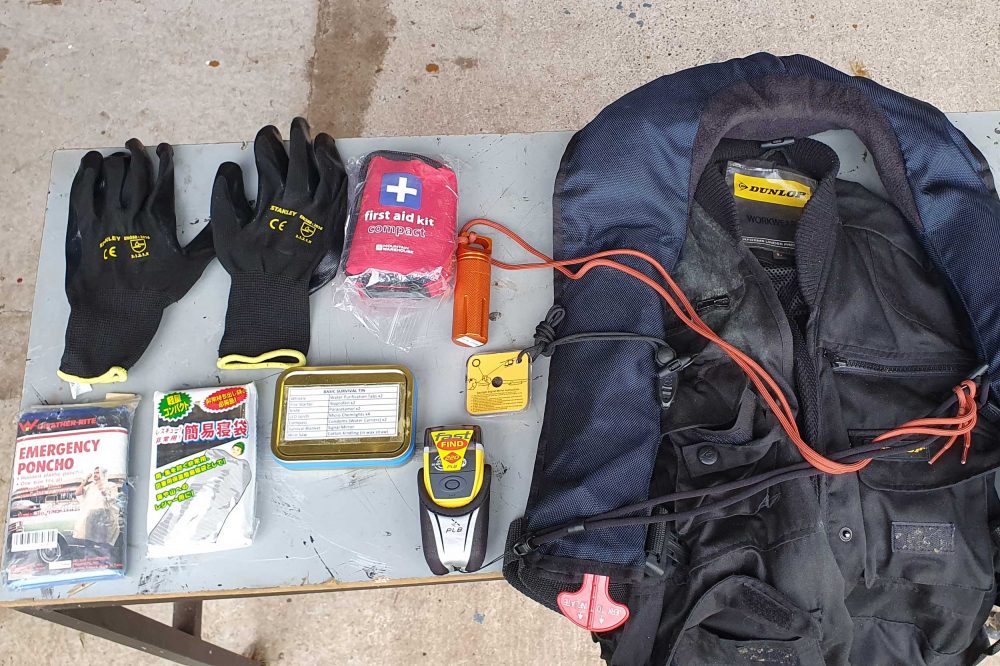

However, where would you carry it? Many life-jackets do not have attached storage pockets, and because the straps are typically stitched on for robustness it’s often tricky to add a normal belt pouch, which would usually slot over a loose end.

Training by the military emphasises that ‘you can only rely on getting out of the aircraft with whatever is attached to you’.

You may have a life-raft and even a buoyant grab bag in the cockpit or cabin, but are you CERTAIN you’ll get them out of the aircraft? After the shock of a ditching? If the aircraft inverts? From a high-wing, when you WILL be egressing from under the surface?

It’s worth thinking about in advance, as uncomfortable as it can be to contemplate. In short, the professional advice I’ve had often over the years is that your essentials should be on you i.e. wear them.

This is one reason why the military insist on the wearing of immersion suits and suitable clothing underneath (the immersion suit only keeps you dry – not warm) when the water temperature is below 15°C, even if there is a life-raft in the aircraft.

2 comments

Please don’t dismiss the humble water-activated dim incandescent bulb. They’ve remained that way for a reason!

LED lights are virtual invisible to thermal cameras, so the dim (battery saving) bulbs are actually more visible at night to SAR sensors.

An LED strobe (or just your usual night flying headtorch) make an excellent addition. Many PLBs have their own built in LED strobes anyway.

Thanks, Dusty – handy info.