In 1934, Harry G. Ballance bought a new Stinson SR-5E and flew it home. In 2006, Harry G Ballance bought the very same SR-5E – and flew it home. The key, of course, is that both of the ‘Harry G Ballance’ are different men. Harry G Ballance Senior was the original owner of NC14572. The current owner of the Stinson, now known as Miss Scarlet, is his son, Harry G Ballance Junior. And the 72 years in between tell a good story.

Harry Senior learned to fly in 1928 – the year after Lindbergh set off an aviation mania in the US – and by 1934 was already something of Stinson aficionado. His motion picture distribution business required him to travel extensively throughout south-eastern US and the distances almost prohibited travel by rail or car. After all, his territory was just slightly smaller than France, so flying became essential to the meet-and-greet style of his profession. He began using a Stinson SM cabin monoplane to cover the miles. He chose well.

The Stinson company had been founded in 1925, when movers and shakers in the Detroit business community decided to back a new venture, headed by one of America’s best known pilots, Edward A ‘Eddie’ Stinson and his business partner/promoter William Mara. The Stinson family was prominent in American aviation from almost the beginning. Although Eddie eventually became the highest time pilot of his day, the family name became famous through the efforts of his sisters Katherine and Marjorie. These women, accomplished pilots before WWI, gave flying exhibitions all over the US and Canada, and ventured as far as Japan and China. They also taught hundreds of men, and a few women, to fly – but not their brother Eddie. They considered him to be too fond of drink and ‘loud living’, and although they valued his services as a ‘mechanician’, they didn’t want him anywhere near the cockpit of an aeroplane. He eventually found another instructor.

Stinson had had his fill of freezing in open cockpits, and had seen the toll they had taken on his sisters’ health. He proposed an enclosed cabin biplane, with comfortable seats, an electric starter and a heater. When the first ‘Detroiter’ was built, Stinson was able to demonstrate it to potential clients, even though it was winter in Detroit. After a couple of sales to wealthy individuals, the new company was off and running, becoming one of the best selling marques in the country.

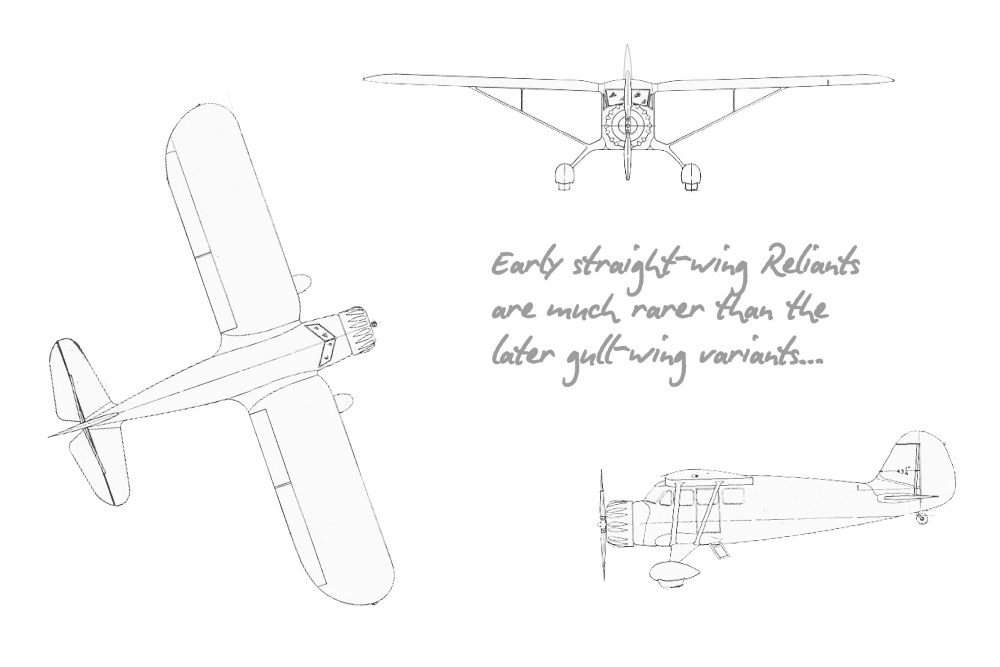

In 1927 the new SM (for Stinson Monoplane), also known as the ‘Detroiter’, replaced the biplane. Supported by a constant-chord, strut-braced high-wing. The cabin was easy to enter (hefty welded footsteps became a Stinson earmark). Power was supplied by any of several radial engines: Curtiss, Warner, Wright, Pratt & Whitney… there was even one with a Packard diesel. The SM line proliferated through a wide range of versions and sizes but all of them retained the ‘straight’ wing.

In 1929 Mr E L Cord entered the picture. After making his fortune selling glamorous and expensive motorcars, Cord decided to spend his way into the business of the future – aviation. One of his holdings was the Lycoming Motor Co. Lycoming produced high-quality, straight-8 engines for Cord cars and was just finishing the development of a nine-cylinder radial aircraft engine, which seemed ideal for the aircraft that Stinson was producing. The merger provided Stinson with the ability to keep prices down, which became essential just a few months later when the stock market spun in, and provided capital to improve the product.

The new model became the Reliant. Known as the SR series, by 1934 it had progressed to the SR-5, with an improved landing gear, a lovely bump cowl covering a 225-240hp Lycoming engine and a complete novelty, ‘speed arrestors’. Now known as flaps, they allowed Bill Mara, who flew many of the sales and demonstration flights, to land in a little over 200ft!