All of this may – or may not – be mentioned in the sitting part of the tour, which is an excellent half-hour talk given by park rangers in the small visitor centre.

I say that because I’ve attended this talk at least a dozen times and each time it’s different, often tailored to what the ranger senses the audience may know or not know.

I’ve watched ranger Darrell Collins give the talk a half-dozen times, he’s been at the Wright Memorial since 1977. Encouragingly, when I asked how the audiences have evolved during the past decade, he told me his impression is that they’re more educated now than four decades ago, with a greater sense of curiosity.

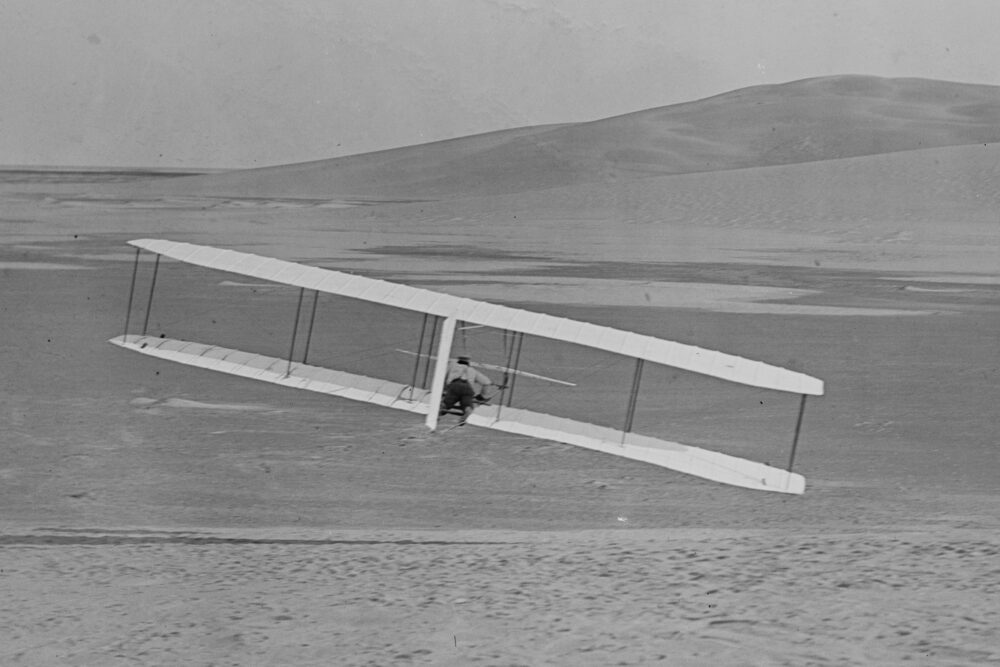

Regardless of variation in detail, the ranger’s lecture will always get around to what the Wrights did achieve: the first documented powered flight of a heavier-than-air aircraft from level ground and under complete control.

Others had flown before the Wrights, including powered flight. And in the US, a controversy continues to simmer on whether Gustave Whitehead, a German immigrant engine builder living in Bridgeport, Connecticut, actually demonstrated powered flight as early as 1901, two years before the Wrights.

Based on the work of historian John Brown, the august Jane’s All the World’s Aircraft recognised Whitehead as the true pioneer in controlled, powered flight. And the evidence is too compelling to dismiss out of hand, although it doesn’t equal the documentation available on the Wrights’ work.

It’s quite likely that first-flight credit still goes to the Wrights because of their careful documentation, and especially photographs, and because in 1908, the brothers electrified France and the world with flight demonstrations unmatched by anyone else.

Whitehead was still active then, but not garnering the attention the Wrights were, plus a year later, the notorious patent fights that dogged the Wrights for years temporarily stunted competitive development.

Utterly birdlike

Who was first in flight may never be proven beyond doubt, but one thing that’s not open to challenge is that, like the scientists they in fact became, the brothers richly documented their work with diaries, notes and photographs, including the now iconic first flight image of Orville’s take-off snapped by a startled surfman, John Daniels, whose training in photography consisted of Wilbur explaining how to squeeze the shutter bulb.

That image forms the background for every US pilot certificate yet today.

The Wrights’ legacy is documented, methodical research that became the foundation of modern aerodynamics.

Ranger Collins reminds audiences that the Wrights’ understanding of adverse yaw and their coupling of the rudder to roll input to counter it is a design principle still used today on the Boeing 787, to name just one example of a design dependent on Wright documentation.