My grandfather Walter Bowles was a ‘throttle bender’ – one of a small group of pilots who were regular competitors in the air races of the 1950s and who pushed their machines, including the throttle lever itself, to the limit. Hence the name ‘throttle bender’.

During one of those races, the crankshaft of his Miles Messenger gave way and the propeller departed to a destination unknown. He landed in a field (the Messenger has a stall speed of around 28mph) and a few days later, after the Miles factory had replaced the engine, he flew it out of the same field.

Some months later the prop was found in a wood, and the local police returned it. Years later, and inspired at least in part by his flying exploits, I too learned to fly.

With around 550 hours under my belt, I set off from Gloucestershire Airport early one morning in August 2019 for a business trip to Dublin. I was flying our group Piper Turbo Arrow III. The day was perfect, and a fairly direct route over mid Wales and south of the Llŷn Peninsula took me to Weston Airfield, west of Dublin, in just an hour and a half.

Over the sea at 10,000ft, l was aware of how far it was to land, and which way I would go ‘if the engine stopped’. But it didn’t, and the rather exciting approach over central Dublin up the River Liffey had me safely at Weston.

Later that day I set off for home, planning to fly down the Irish east coast towards Rosslare and across to Pembrokeshire. Conditions were VFR all the way, and I climbed into Irish Class C for the sea crossing at 10,000ft. The flight was uneventful until around midway across the sea. I thought I noticed the original Piper CHT gauge flicker. But it was reading ‘zero’.

I tried to remember whether it usually had a reading, but because I tend to use the JPI engine monitor, which gives a reading for each of the cylinders, I assumed it was disconnected.

A little later I saw it flicker up to the middle of the green range, so clearly it would normally work, but then it reverted to zero. I checked the JPI readings which were normal, and I put it down to an electrical fault (which in a way it was) and continued.

Landfall came 10 minutes later and I remember thinking RAF Brawdy would make a good emergency landing field if one were needed. But the engine sounded fine, and instruments were all ‘in the green’… except the cylinder head gauge. Ten minutes later I smelled smoke. Looking around for a moorland fire I could see nothing. Engine instruments OK. Must have been some smoke from a fire I couldn’t see. I didn’t make the connection. Another five or 10 minutes passed.

Then it happened. The engine went from lovely smooth warmed-up 6-cylinder Continental to sounding only a little less rough than starting it on a cold morning. Clearly it was misfiring. I checked fuel flow, magnetos, mixture and anything else I and the checklist could think of. Nothing obvious, but it was clearly not happy. I pulled the throttle back from 32in to 25in to reduce load on the engine and made a Pan call to Western Radar.

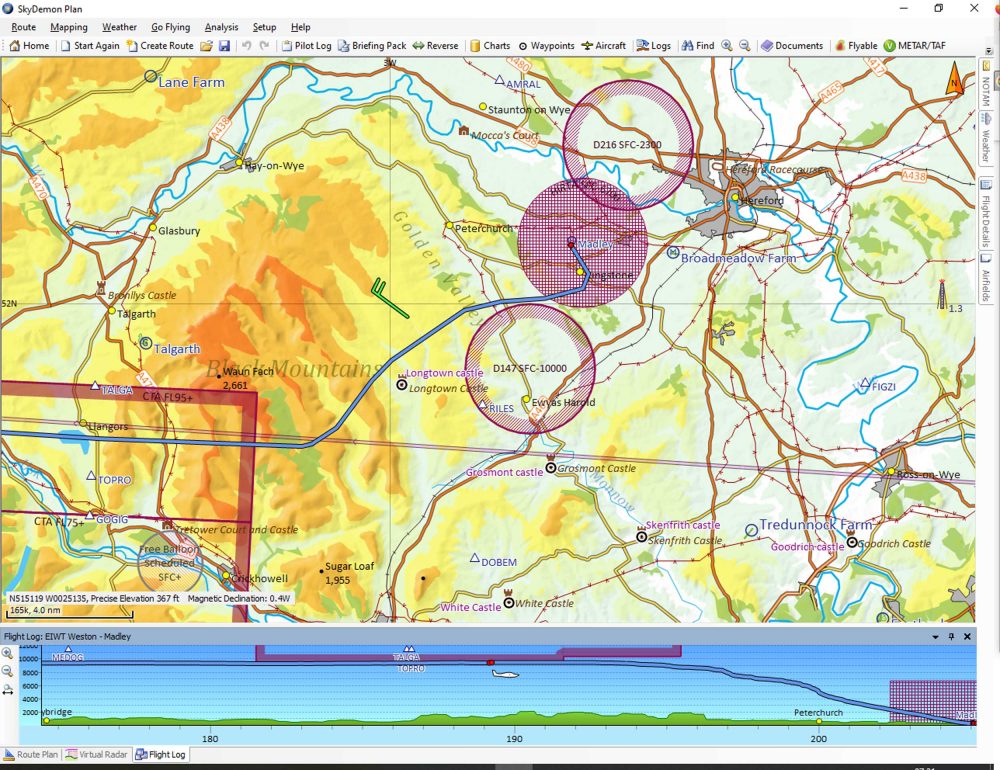

Could I have a QDM to the nearest airfield please? Shobdon was 20 miles north-east. It was nearer than Cardiff and I didn’t want to try to nurse it all the way back to Gloucester. It was only about 10 minutes flying time. They’d be closed, but who cares? It’s a hard runway that’s easy to find. Western gave me a heading to steer.

I can’t remember whether I decided to descend, or whether with a light throttle and a malfunctioning engine I couldn’t maintain height. Either way, I began descending. Then I smelled smoke again and thought I saw some in the cockpit.

4 comments

Wow, great reading, glad it all worked out for you .

“If it had been for real I’d have undershot the field slightly. As we climbed away, we talked about what to have done, and his advice had been to push the nose forward a little, gaining speed and then at the last minute convert that speed into height. ”

I’ve heard this suggested a couple of times. But if you’re already flying at best glide, pushing the nose forward will mean you undershoot even more, and you won’t make up for it with the extra speed.

Paul

Excellent write-up, thanks. I take Paul’s point about best glide and would agree in a stabilised descent. But in the final stages of a landing, I think it’s more about dynamic energy management than a stabilised flightpath. You do what you have to do to make a safe landing area and avoid obstacles – which it seems is what you did, and it worked. Stuff that works beats simplified theory, I guess!

@davidwhite894 that’s my understanding. Paul Ruskin my sense was that pushing the nose down and then “hopping” over the fence meant the round out was shorter and I landed more slowly. Having used the energy to prolong the glide in a way that pulling the nose up earlier would not have done. Anyway, it worked…. Of course it’s possible that maintaining best glide might have worked too. But with advice from a CFI with 14,000 hours ringing in my ears, I followed it 🙂