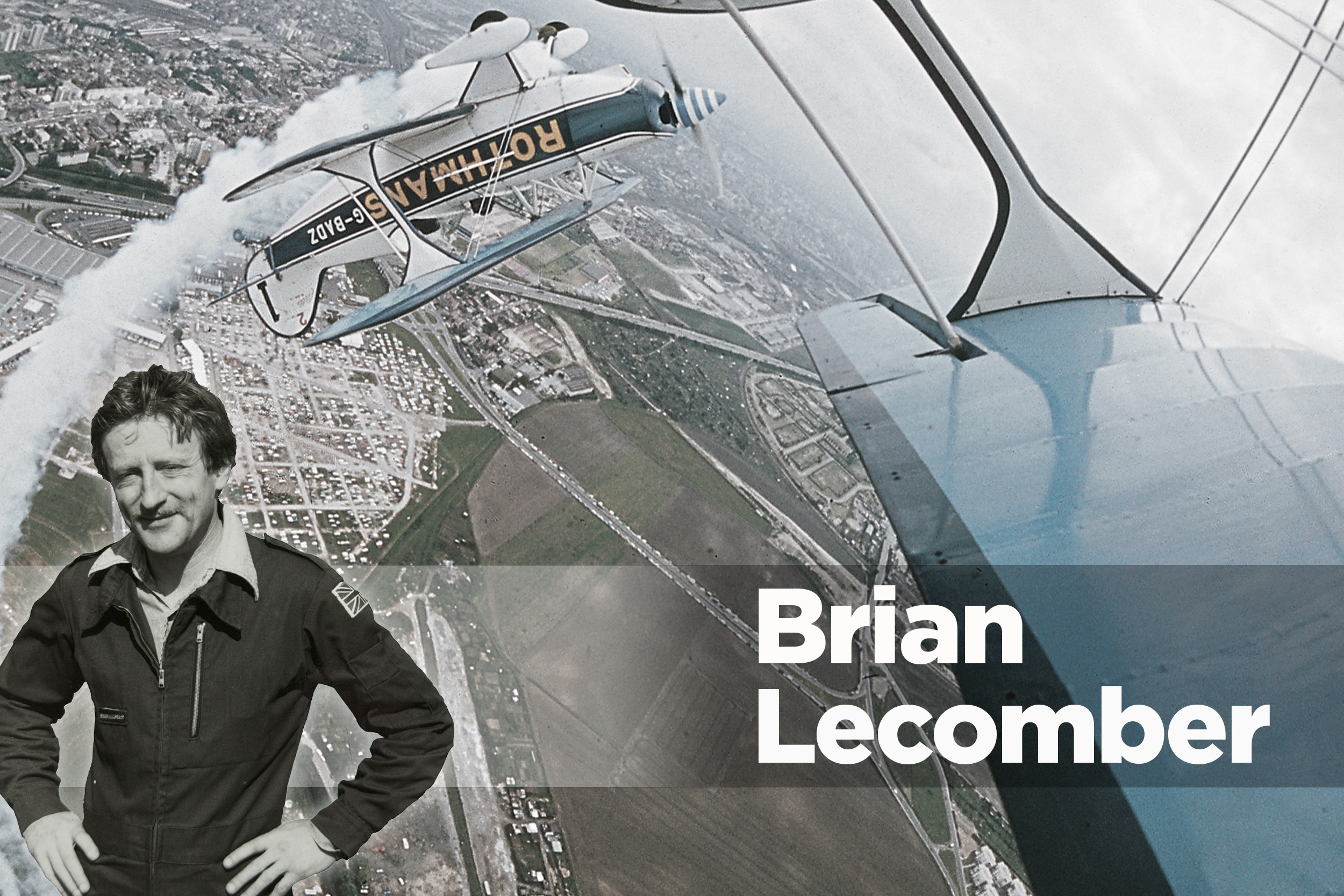

Back in 2013 Brian Lecomber wrote his last column for FLYER. He passed away in September 2015, leaving the world poorer for his absence, but richer for the memories and writing he left behind. Brian spent many years on the circuit as a very accomplished member of the Rothmans aerobatic team, and of his own Firebird Aerobatic team.

In addition to his novels, Brian wrote about motoring and, of course, aviation. We’re reformatting his previous FLYER columns, this appeared in FLYER in April 2013.

Who were the bravest group of pilots in the world? At any time, in any place, in the whole five score years and ten

of aviation?

Of course the candidates are legion and far more than legion. A man could cite the very early pioneers of flight. Or the flyers of WWI with their desperately short lifespans over the Western Front.

Or the record-setters of the ‘tween-war years. Or the RAF pilots of the Battle of Britain.

Or the night and day Allied bomber crews of WWII, with their own horrible attrition-rates. Or the chopper pilots in Vietnam. Or the… or the…

No – our world aloft has never been short of raw courage, both by individuals and en masse. So who were the very bravest?

Of course I do not know. And anyone who purports to know runs the risk of being labelled an armchair academic with no personal blood-and-guts and strap-bruised experience. Well, I am not an academic. But I do have strap-bruised experience. And I do have an opinion. I do not for one moment expect to foist it upon others – but I do have an opinion.

A maybe heretical opinion. If it offends – well, so be it.

I believe the bravest group of flyers in the history of aviation were the aircrew of the German Luftwaffe in the last year of WWII – May 1944 to May 1945.

I also feel that, despite the vast majority of us not having been a gleam in our parents’ – or indeed grandparents’ – eyes at that time, we can all still learn from them. I’ll come back to that.

Some may say that the Japanese Air Services of the same era were even braver – and that may be right. Certainly they faced a similar degree of problems as the Luftwaffe (although mostly more maritime of content) and attempted to solve at least some of them with the most desperate expedient of all – kamikaze (suicide) attacks.

I confess I don’t have the faintest insight into the Japanese mindset of that period. Any group of aviators (whether volunteers or not – a subject of historical argument even to this day) who will sacrifice some 4,000 – four thousand – pilots and aircraft in suicide missions is so far removed from our Western thinking that comparison is not possible.

And how any nation could define this mass suicide as ‘Divine Wind’ (the literal interpretation of kamikaze) and then go on to name their most dedicated kamikaze aircraft (nothing short of a manned bomb) the Ohka is utterly beyond my comprehension – the word Ohka meaning, of all things, Cherry Blossom. You figure the thought process out. It is beyond me.

Whether it was beyond the Luftwaffe in the last year of WWII – well, again I’ll come back to it.

What is certain is that the life of a Luftwaffe pilot in that fateful last year was very much less than divine or blossomy. If you are a raw pilot just out of flying school with maybe 150 flying hours – about half that of the new boys of the Allied forces – your prospect is at best dismal, and at worst… well, a lot more than dismal. Young Kurt may have achieved his lifetime’s ambition by being posted to a fighter Staffel, but having arrived he will quickly encounter certain realities…

The first is the terrible paucity of fuel. Allied commanders, most aware that fuel is the lifeblood of any pugnacious endeavour, have placed German oil refineries very, very high on their ‘most wanted’ bombing list. With a considerable degree of success.

In April 1944 the Reich produced 175,000 tons of fuel. In June the total was down to 55,000 tons.

Young Kurt will not know these figures. But he will see the fuel bowsers driving out of the aerodrome daily on the dreary round of visiting all the fuel depots within reach and pleading out 5,000 litres here, 2,000 litres there…

So no Staffel familiarisation for Kurt. The first time he leaves the ground he will be in action.

If, that is, he can find a serviceable aircraft to fly. Which, in 1944 and ’45, very much depends on the German railways.

In theory, in 1944, Germany will have produced 40,000 new aeroplanes. But the lack of fuel being what it is, they are not normally flown to their operational bases, but partially dismantled and loaded onto trains. Which the Allied forces then bomb, machine-gun and rocket until the German rail system virtually collapses. With the aircraft and spares on board.

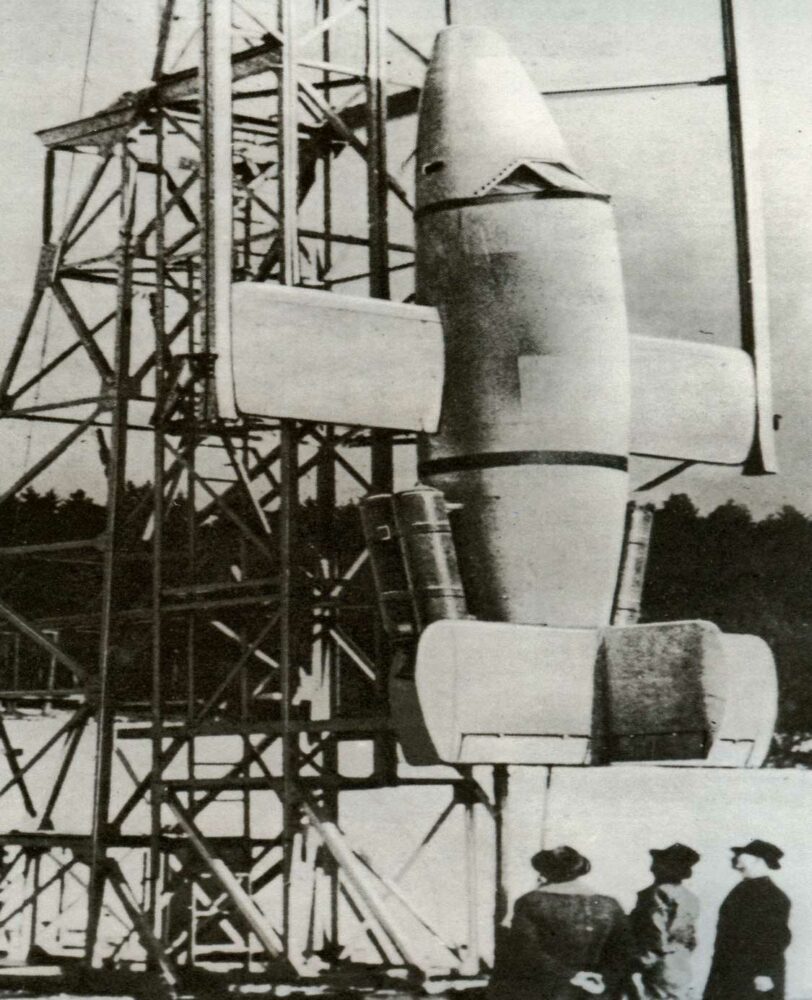

The effect of this is vast. For example, something like 1,400 Messerschmitt 262s – the world’s first operational jet fighter – will be manufactured, but the Luftwaffe can at best only ever muster about 200 to actually fly.

The rest are stuck on the railways or awaiting new motors – a most frequent occurrence since the early German jet engines have a life-span of between three and 12 flying hours. And of course the replacement engines are also stuck on the railways…

What Kurt does know is that the only thing there is no shortage of whatsoever is enemy aircraft.

The heady blitzkrieg days of 1940 are now very, very long gone. In 1940 the Luftwaffe dropped 37,000 tons of bombs on England. In 1944 the RAF and the USAAF will drop 650,000 tons of bombs on Germany…