AAIB safety message

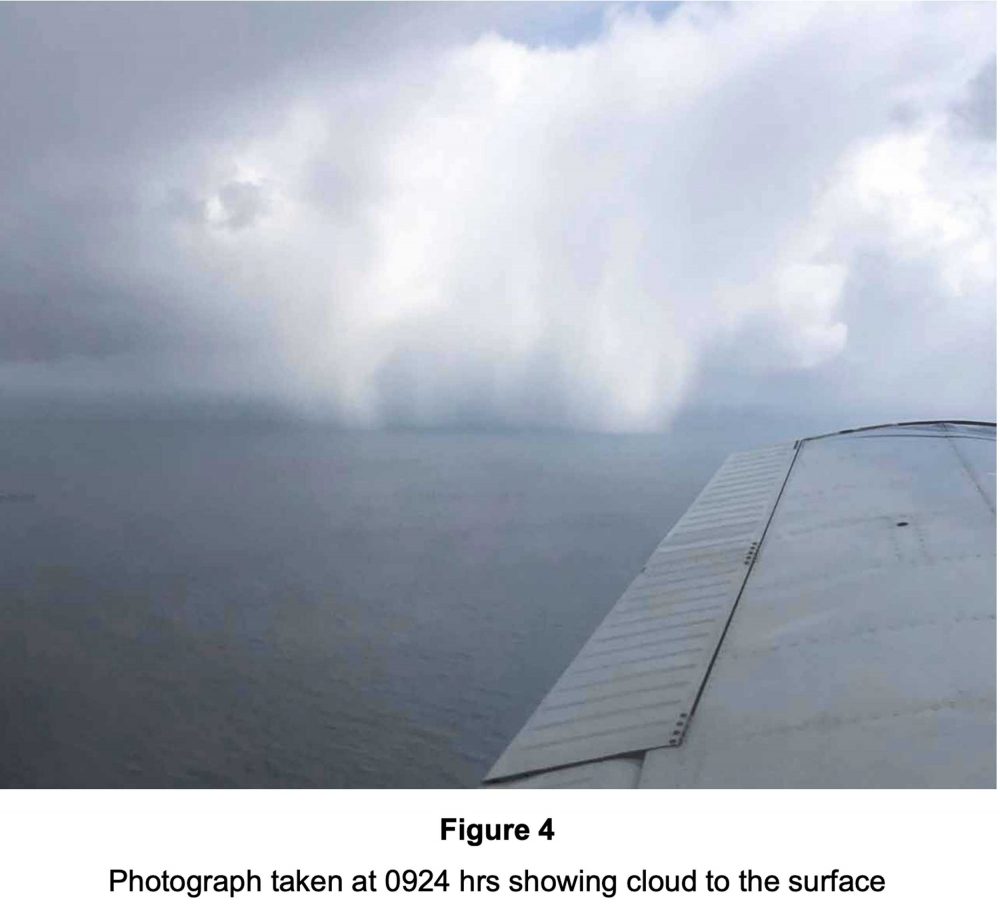

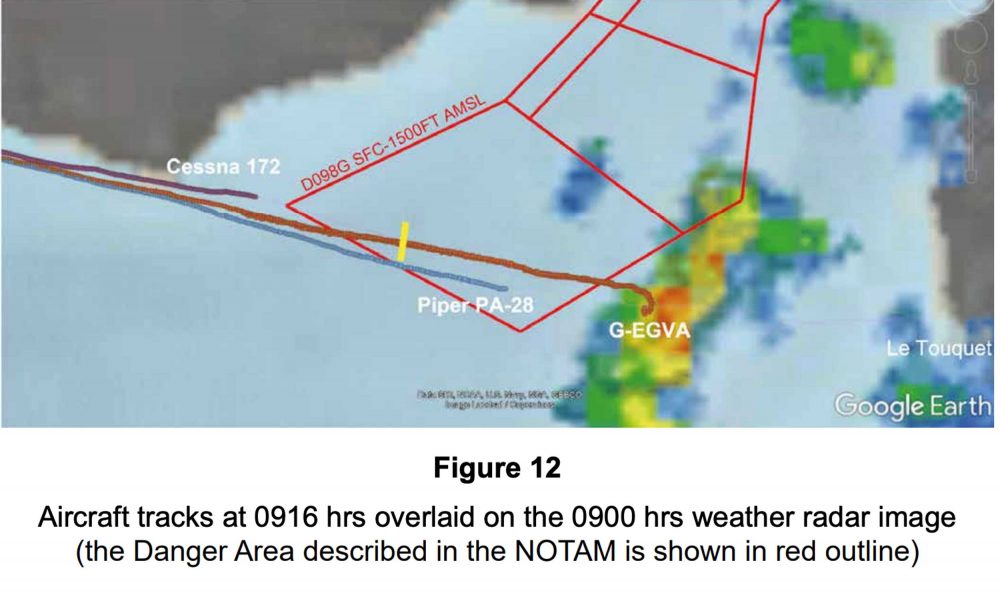

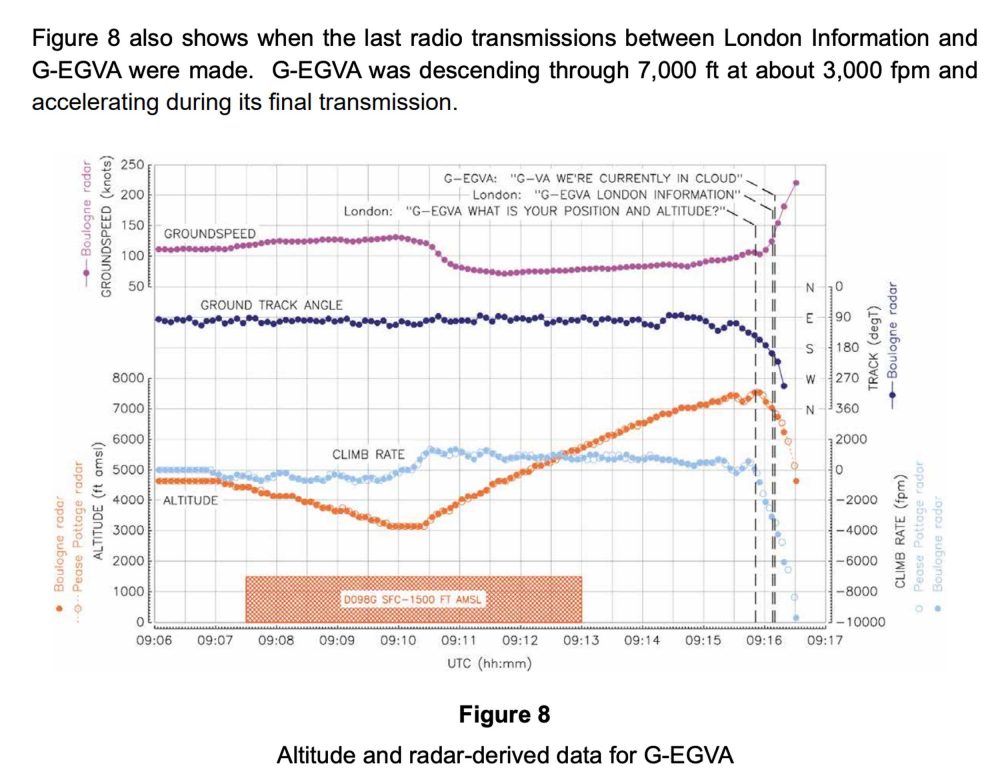

The evidence available to date indicates that control of the aircraft was lost when it entered a highly active cumulus cloud, which had been forecast. Neither occupant was qualified to fly in IMC. It is likely the aircraft was substantially damaged on impact with the sea.

Nick’s Analysis

It is very dangerous to enter cloud when not suitably qualified or when not in current practice in instrument flying. The AAIB has investigated numerous accidents when control of an aircraft was lost after intentionally or inadvertently entering cloud in these circumstances.

This tragic and sobering accident started with an airfield fly-out that should have been an enjoyable day out to Le Touquet. There were some credible decisions made that day: some pilots were able to route themselves around the bad weather to make it to Le Touquet. Another pilot decided that the weather was unsuitable and diverted to Shoreham. Sadly it looks like the crew of VA made the wrong decision with fatal consequences.

The safety message made in the Special AAIB Report says much of what needs to be said: ‘flying in cloud should not be attempted by those who have not been trained in instrument flying, or who are out of practice at this skill’.

I have been fortunate to have undergone disorientation training during my military career using clever ground-based devices that are able to demonstrate remarkable disorientation effects by fooling the body’s senses. I have also experienced disorientation during both night and IMC flight, such that my body’s senses have been screaming at me that I simply must be in a different attitude to that which the instruments are telling me: the so-called ‘leans’. In these cases I have fought the ‘seat of my pants’ feelings and followed the instrument indications, but sometimes it was not easy.

With experience in GA aircraft, military fast-jets, and commercial airliners, there is no doubt in my mind as to which are the hardest aircraft to fly in IMC: undoubtedly GA aircraft.

The reasons are many:

• Low weight and low wing-loading With their light weights, GA aircraft are less stable and more prone to turbulence – especially in convective cloud. The thick wings of GA aircraft also make them more prone to icing.

• Poor instrumentation Flying precise attitudes on a small vacuum-driven Artificial Horizon (AH) is not easy.

• Low speed Low speed means that you remain IMC for longer, with more exposure to effects such as engine and airframe icing. The low speed also means that any small angle of bank will lead to a significant and unwanted heading change if not noticed quickly.

• Low power Most GA aircraft are relatively low powered. This leaves few options to climb out of cloud if that is thought to be an option. There is almost certainly no chance of out-climbing convective cloud.

• Lack of weather radar or other on-board, look-ahead weather equipment Without the ability to see embedded convective cloud while IMC (CU or CB), there is the chance of blundering into these dangerous cloud types.

• Lack of de-icing equipment Most GA aircraft are not cleared for Flight Into Known Icing (FIKI) conditions. Icing is a major concern during IMC flight – I have a number of Canadian pilot friends who all have scary stories of getting iced up in IMC flight, sometimes to the point of being unable to maintain height.

Having mentioned those factors (and there are many more), there is still a major place for GA aircraft to operate in IMC conditions, but not without training in both theory and flying. IMC pilots must have (among other knowledge) a sound knowledge of practical meteorology: the PPL syllabus is a good start but further understanding is always better.

Various qualifications are available for pilots who wish to fly IMC, namely the Instrument Rating (Restricted) (Part-FCL parlance for the IMC Rating), the Competency-Based Instrument Rating, and the full Instrument Rating.

The IR(R) remains a popular qualification for UK-licenced pilots but it is not recognised outside of UK airspace. There are arguments on both sides as to whether the IR (R) should be used as a day-to-day IMC qualification or as a ‘get-you-out-of-trouble’ ticket if you get caught in cloud. Even if you don’t have the interest or finances to undergo a full IR(R) course, there is a lot to be said for undergoing at least some training in instrument flying.

This training could get you to a stage where you can overcome the startle factor of accidentally entering cloud and getting yourself out of the cloud sensibly and under control. A 180° turn on instruments is a requirement for PPL training but more training will always be beneficial. A bit of instrument flying training would form an excellent basis for a two-yearly instructor flight for rating revalidation purposes.

Instrument flying is far harder than VFR flying. The workload is always higher and there are far more requirements in decision-making, prioritisation, and procedures. Please don’t assume that a few hours on a PC flight simulator is any realistic representation of genuine IMC flight.

For those who have started training towards an instrument qualification, or indeed those already qualified, I would offer the following advice as the basis of successful instrument flight, under the banner of the so-called Selective Radial Scan:

• Aircraft attitude comes first, so your focus is ALWAYS the artificial horizon to ensure that the attitude is that which you require. If it’s not, then fix that first.

• Aircraft speed is the next priority. It’s no good having the correct attitude without the right speed (i.e. not too much and not too little).

• Altitude is next. When in IMC you must always know what your current safety altitude is, and make sure that you are above it (unless you are following an airport arrival or departure procedure, or are under ATC vectors).

Everything else comes after those ‘fly the aircraft’ aspects. The ‘Aviate – Navigate – Communicate’ phrase still applies, but the ‘Aviate’ aspect takes on a particularly high priority in IMC flight. Use of an autopilot when in IMC is particularly useful as a means of off-loading cockpit work.