I was quite happy flying AX3s at Popham. Popham, if you don’t know it, is a delightful airfield set in rolling Hampshire countryside. The landscape around it could satisfy a lifetime of low and slow summer evening flying, buzzing about over fields and streams, out over the scarp edge of Watership Down and above the valley beneath. If feeling brave, I might venture south, out over the blue waters of the Solent and across to the Isle of Wight.

I was happy doing this until one day, there on the grass in front of the Popham café, appeared a thing of beauty: G-BUCO, an immaculate Pietenpol Aircamper built (I now know) by a gentleman called Alan James. Next to it my AX3 looked like, well, it looked like a flying tent. There was no choice. I had to get a better looking aeroplane.

The UK’s Light Aircraft Association has a treasure trove of plans, particularly of the low and slow summer-evening variety of aeroplane. The problem was that the aircraft that I liked the look of – Currie Wot, Luton and Turbulent – were mostly wood and needed to be kept in a hangar. I could not see myself being able to find, let alone afford, an indoor hangarage near London.

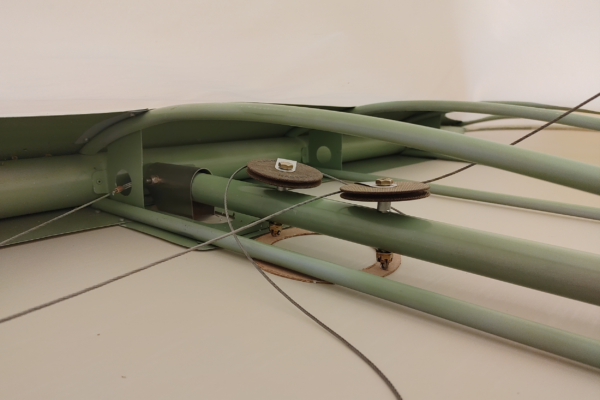

There was, however, a design being built extensively in the US which caught my eye: the Circa Nieuport. I have a particular weakness for anything that could be called a ‘flying machine’ rather than an aeroplane, and this almost perfectly scale replica of a Nieuport 11 (‘Bébé’) biplane falls close to that category. Particularly if one were to cover it in translucent doped linen and omit anything as war-like as a Lewis gun…

As the design was made of aluminium tube, not wood, it would not mind being left out in the rain occasionally, at least during the summer. The only problem, and admittedly it was a pretty large one, was that it was not an approved design in the UK, so it could not be flown here.

In April 2007, everything changed. The Civil Aviation Authority de-regulated single-seat microlight aircraft. I could build the Nieuport if the weight and stall speed fitted within the microlight category.

The first thing I did was to send off for the plans from designer Graham Lee’s son. These arrived from Canada a week later. I was initially disappointed.

Instead of beautiful draughtsman’s blueprints I received a photocopy of a handwritten and hand-sketched series of instructions. However, after reading through them, they were clear, easy to understand and talked the reader through each stage. Overall, it did not look too difficult.

Finding a suitable engine was more of a challenge. The original had flown in the 1980s with a 25hp Cuyuna engine. No such thing existed 30 years later.

Builders in the US had used a 36hp Volkswagen, an excellent engine, but too heavy if I was to keep the aircraft within the UK weight limits. The plans suggested a Rotax 447 as an alternative… these are no longer made. The 50hp Rotax 503 is available, but this was discounted in the plans as being too powerful.

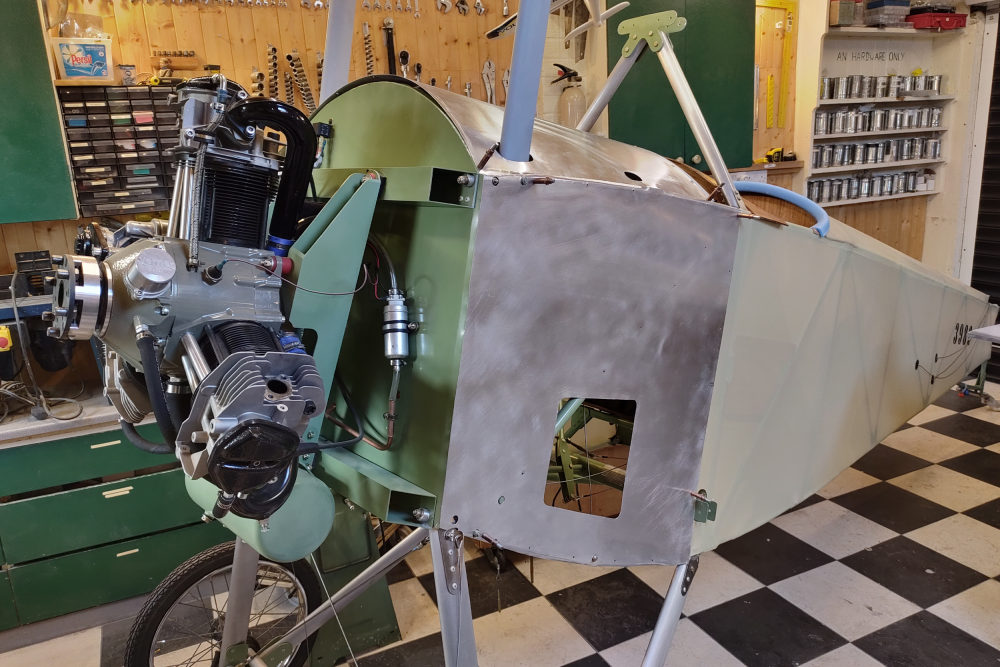

On the internet I had read about an engine called a Verner 3VW. With three cylinders, the empty weight was said to be only 36kg. It produced 36hp, or 42hp for take-off. Better still, it was a radial so it would look right – and a four stroke, so it would sound right.

Learning to build

I needed to learn some aircraft building skills, so I signed up for two LAA courses. The first was about aluminium. In a Portacabin on a windswept and rainy airfield, I learned to use air tools to cut, shape and rivet aluminium, coming away from the day with an aluminium toolbox, and the realisation that I would need to buy a compressor.