I contacted all the handlers at Girona and most responded, except Iberia, and they all wanted almost €300 for any contact.

So, we rang Iberia, with a Spanish translation on hand, and eventually were given a budget of €24.41 x2 for ramp handling and transport of €7.74 x2 + an additional €20 x2 for the security pass. This was a lot more than the expected cost set by AENA, the Spanish aviation authority. However, it was a lot cheaper than the other handling agents.

Iberia needed details of the fuel handler and requested, as per the AIP, that we sought permission from AENA to operate to, and fly from, Girona. I contacted AENA and received its response of approval, which had been cc’d to Iberia in an email. Although no slot is required from the coordination office in Madrid for a visit to Girona, this process was still required locally by the airport.

The refuel company was a little more difficult, as there was no response to any emails. However, when ringing them with a Spanish translation at hand (again), they thought we were at the airfield ‘there and then’. Consequently, we didn’t bother too much with the refueller as we felt sure that Iberia would ‘handle it’.

We also had to fill in a GenDec, kindly provided by a user on the EuroGA website. We sent this as soon as possible to Iberia which forwarded it to the relevant authorities.

Now we knew the destination airport, this left just the accommodation which neede to have reasonable options in case of a cancellation of the GA flight – that can still happen even if you have an Instrument Rating.

After a little deliberation on whether we would stay in Barcelona itself or treat ourselves to a more luxurious, yet cheaper, hotel with a pool in the Costa Brava, Ryan quickly found two Aqua hotels located in Santa Susanna.

We stayed at the Aqua Hotel Onabrava & Spa for three nights at a total cost of £419.37 for the two of us – £69.90 per night, per person. Within the vicinity of the hotel are the beach, many restaurants and a railway with a decent service even on a Sunday to Barcelona city centre.

On this flight, we used a Mountain High System AL-647 oxygen system. This is the first time I had ever used supplementary oxygen, and received a full briefing from the owner along with some additional self-learning of all the functions. The bottle is 3.8kg or roughly 4kg with its padded cylinder carry-on.

I also invested in an MH-3 Flowmeter which is calibrated for use with the Oxymizer™ cannula. With the MH3, you can set the flight level/altitude to the desired level to save oxygen consumption.

According to the cylinder duration chart, at 10,000ft one individual bottle will last 26.9 hours, and at 15,000ft – 14.8 hours. For any other figures, it’s important to interpolate to get a rough figure for the set attitude.

This setup proved its worth, allowing flights under the IFR system that would not have happened because of the distances flown above the weather. To further enhance safety and the ability to outclimb and fly further afield, I plan to invest in a Mountain High O2D2 System (incorporating an EDS, Regulator, and Glass-Fibre Filament Cylinder CFF-048). This is a 3,000psi cylinder giving roughly 83.6 hours at 10,000ft or 40.5 hours at 15,000ft with the EDS. The MH EDS provides oxygen only when you inhale, thus reducing oxygen consumption and doubling the duration available.

Planning for the flights I used Autorouter.aero and roughly seven days before departure gives the ability to see what conditions are forecast. That’s via a GRAMET and an estimated en route flight time which isn’t very accurate, although occasionally can be. Confusing, I know.

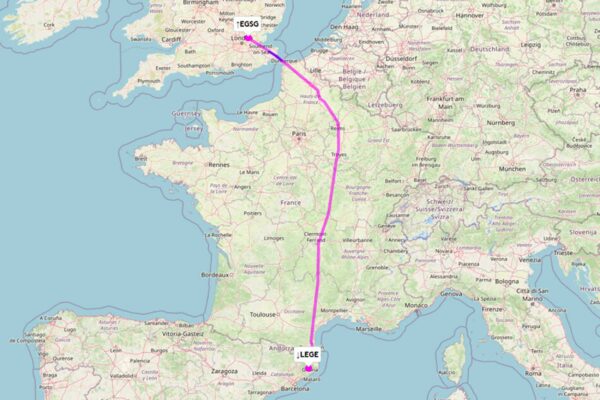

The quickest route was 4hr 30min out of Stapleford via Detling (DET) avoiding Gatwick and down via Le Havre, west of Paris and Limoges, Perpignan, before finally crossing into Spain via a waypoint called KANIG.

As the day of the flight got closer, the weather became a little more impractical. We could either depart well ahead of the front early in the morning, or depart after but face the difficulty of stronger than forecast winds which meant a longer flight or a stop for fuel, which in turn would add almost an hour.

I’d been warned that flying in fronts isn’t comfortable and have flown in a fair few weak affairs, especially cold fronts in the autumn and winter. It’s not just turbulence you have to worry about, but icing, even in summer.

With stronger winds on the routing due west of Paris, I refiled via east of Paris, which meant a delay due to the front and would put us into the mix of the next front, meaning a fair amount of active Cbs.

I initially elected to delay my flight due to not wanting to fly in the front and be in thick IMC for an hour of the flight.