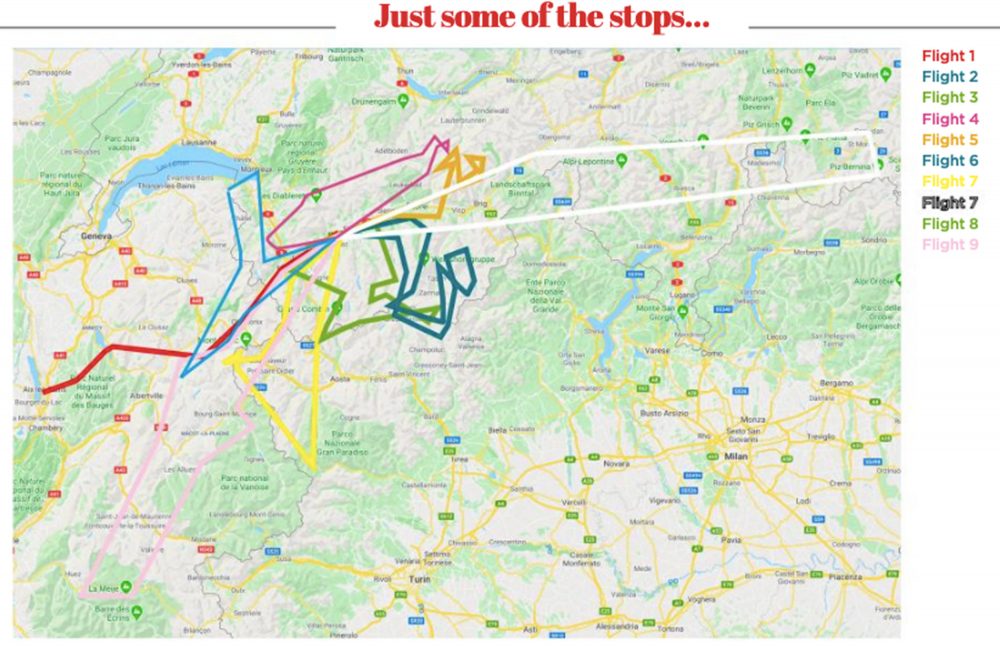

Just south of Verbier I managed to see some more glaciers and peaks peeping at me at 9,000ft. On clearing 10,000ft Grand Combin exploded into view with a bang. Awestruck, I flew around the peak, reaching about 14,000ft, with clouds forming and dissipating below.

While that was all that I expected, it was not all that I saw. The Matterhorn was clearly visible to the east, with a sea of undulating rocky summits, clouds and glaciers beneath. If there ever was gnarly territory to fly over, this was it. I pointed the nose to the east, arriving at the Matterhorn for the first time at summit level (14,692ft), circling the majestic peak, and then looking straight down on the summit. Both Grand Teton, Wyoming and the Matterhorn look very similar from the south-west in the Cub.

The Matterhorn isn’t the only salacious attraction near Zermatt in the aircraft. It is an epicentre of 4000ers, of which I enjoyed a few, including Dent d’Herens (13,684ft), Dent Blanche (14,295ft), Ober Gabelhorn (13,330ft), a bit of Dufourspitze (15,203ft) and the like.

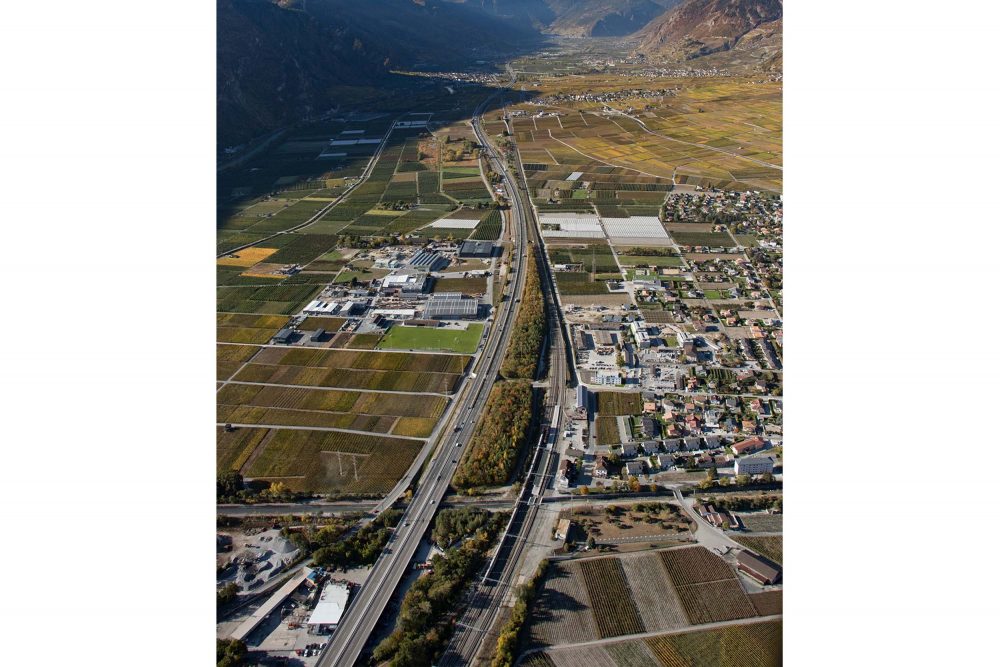

After an evening swirling over glaciers and peaks above the clouds, it was time to get back to Sion, as 8pm was the airport’s closing time in the summer. Besides, I could barely feel my fingers, as I forgot to bring gloves. I should know that 15,000ft is bitterly cold, even in summer, though take-off temps of 28°C do something to the mind. I found a hole in the cloud deck, swirled down below, and cruise descended in a majestic and steep valley, watching chalets go by on both sides. You have to love Switzerland…

My next flight attempt exposed the fact that one of the magnetos completely died on the prior flight, so much so that the engine wouldn’t even sputter on it. It is a sobering thought what could go wrong, though ‘that’s what dual ignition is for’ – at least that is what I told my wife. With it up and running two weeks later, I was able to get into the air after a summer snowfall down to 9,000ft, where I conquered the Jungfrau (13,642ft) and surrounding peaks. On the south side of the Jungfrau lies the Aletschgletscher, the longest glacier in continental Europe, at 14 miles long. Whatever majesty I perceived on Mont Blanc was smashed by the magnitude of this monstrous feature, which I confess induced fear, and stayed rather high above it.