Flying from Greenland to Iceland covers 400nm of the Atlantic Ocean. The weather had deteriorated to well below minimum visual flight rules (VFR) conditions – and I was 100ft above the water with practically zero visibility, flying off instruments and suffering with a headache from hell…

Rewind two-and-half years – and I was learning to fly gyroplanes at my local airfield at Popham (EGHP) in Hampshire, England. It was a sunny day and I mentioned to my instructor, Steve Boxall, that I was thinking about flying around the world. The look on his face was priceless!

“You’d better book some more lessons then,” he replied. So I did. The idea of flying around the world had been in my head for a while. Ironically, it wasn’t the flying that I craved, more the adventure.

Ever since I was young I’d had an interest in flying, but always thought it was for the super intelligent and wealthy elite – and I fell a long way short.

Notwithstanding all that, I decided I was going to find a way to learn to fly. Anyone who has seen a gyroplane might worry about its sturdiness, plus the fact it’s open to the elements, so why opt for a gyro at all then? Despite a few attempts nobody had ever successfully flown around the world in a gyro. After all, there are plenty of people who have flown around the world in helicopters and fixed-wing aeroplanes, but I wanted to do something a little bit different.

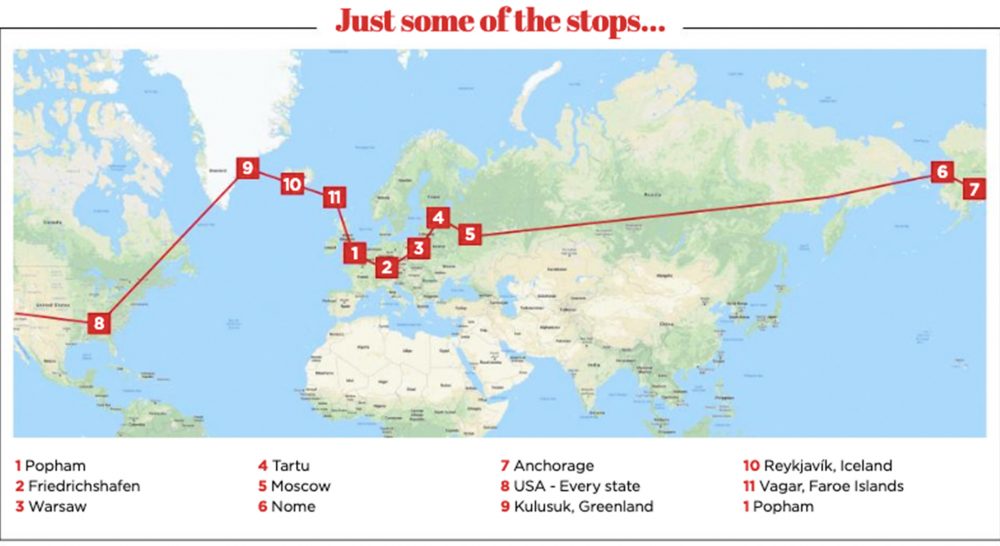

“Planning the route around the world was a complicated task, I wanted to route through Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Dubai, Pakistan, Thailand, Japan, Singapore, then up into Russia – but Pakistan had shut all its airspace down a month before I was due to go”

Just getting to the ‘start line’ and raising the funding I needed was by far the hardest part of preparing for the trip. I was not in a position to self-fund it so had no choice but to raise sponsorship if I was to make the whole thing happen.

The aircraft I chose was the Italian-made Magni M16 tandem trainer. I had learned to fly in this aircraft, and it’s incredibly stable and known for its fantastic reliability. The Magni family were extremely kind and supportive about my plans to fly around the world. Despite having many setbacks, the most frustrating was securing a sponsor, enabling me to buy the aircraft, only then having them pull out. But it was all part and parcel of the project… However, I managed to acquire the aircraft in the summer of 2018 and paid for it up front, which meant that the trip was now on. But had I bitten off more than I could chew? Quite possibly. But my motivation for the trip was at an all-time high.