It’s 8pm on a Friday night, and in the golden evening light, under a cloudless Italian sky, I’m strapping myself into a very exciting helicopter indeed. The Zefhir is the first of its kind. A two-seat, ultralight helicopter with a turbine engine and a ballistic parachute. Developed and built by Curti Aerospace, it has the potential to revolutionise helicopter safety – and a whole lot more besides. Only three have been built so far, and I’m flying one of them with Curti’s chief test pilot, Matteo Pozzoli.

The story so far…

In the moments leading up to the point that I get my hands on the controls of this beautiful little helicopter, I chat with Mirco Cantelli, Curti’s delightful Chief Marketing and Business Development Officer, about the Zefhir’s journey so far. Curti Aerospace, part of 70-year-old Curti Industries, is a family company based in Italy’s renowned ‘Motor Valley’, an area also home to the likes of Ferrari, Lamborghini and Maserati. They’ve been making parts for Leonardo Helicopters (which now make the AgustaWestland 109, among others) for more than 40 years, and the owner – Mr Curti himself – is a big fan of helicopters.

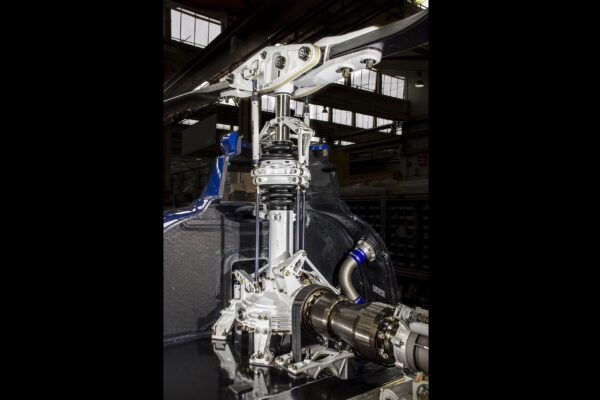

Having decided he wanted to make his own, and having established that Leonardo wasn’t interested in building a small helicopter, Mr Curti did some market research and hired, to supervise his engineers, someone who knew a thing or two about designing helicopters… none other than the (retired) Chief Product Engineer of the AW109.

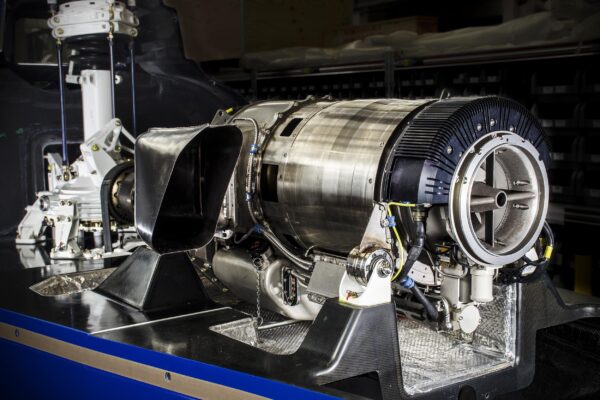

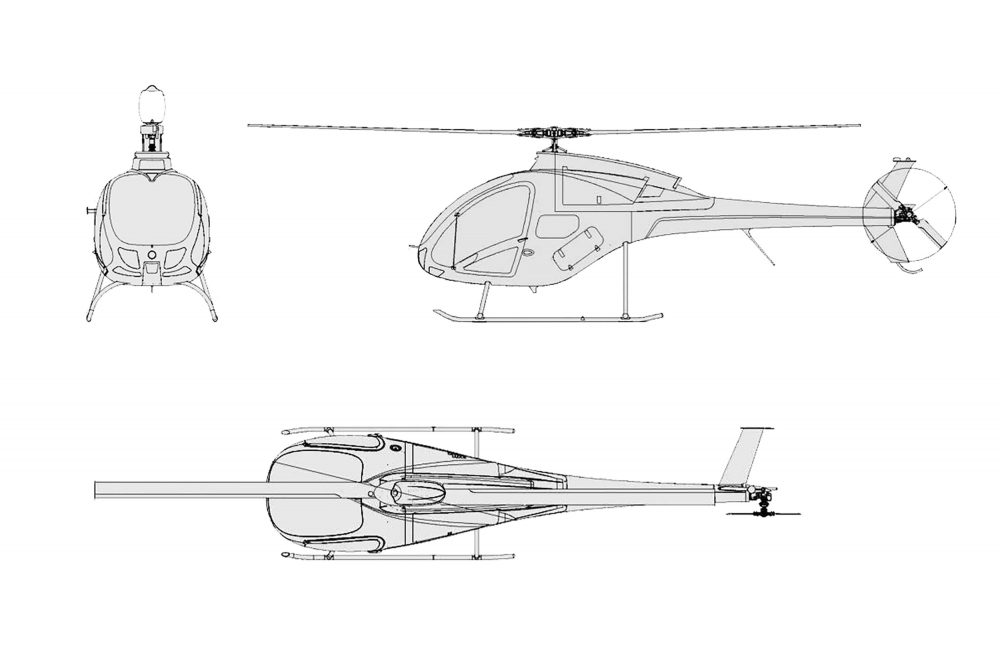

“From the beginning, the Curti Zefhir was very unconventional, because first, we proposed to make a very beautiful external design,” says Mirco. “Three designers from the Bugatti team designed it. Then, we went inside and thought about how to make it very well stabilised and high performance. We also went to the Czech Republic to get the PBS TS100 turboshaft engine.”

The result is an elegant, meticulously designed turbine helicopter with a maximum take-off weight of 600kg (1,322lb), making it an ultralight – a category seen elsewhere in Europe but not, as yet, in the UK.

So, about that parachute.

“After researching helicopter accidents, we discovered that around 90% of fatal accidents were because for different reasons, the pilot was not able to make an autorotation,” Mirco explains. “So, we developed the idea of a parachute and finally, in 2018, we were the first in the world to test a helicopter with a parachute.”

1 comment

And the empty weight?