Raoul Severin’s design is damned clever as he’s made use of modern technology, materials and constructional methods which simply didn’t exist when the original Stampe was designed and built. Furthermore, he’s covered the aircraft with Oratex, which is supplied pre-coloured, so requires no dope or paint, and saves between eight and twelve kilos when compared with conventional fabric.

Then there’s the well-tried Kiebitz constructional method, incorporating pre-formed aluminium materials that any homebuilder can work with. Also, the degree of authenticity in recreating the original Stampe form is so great that, when flying the SV4-RS, the pilot can look out and feel like they’re in an original.

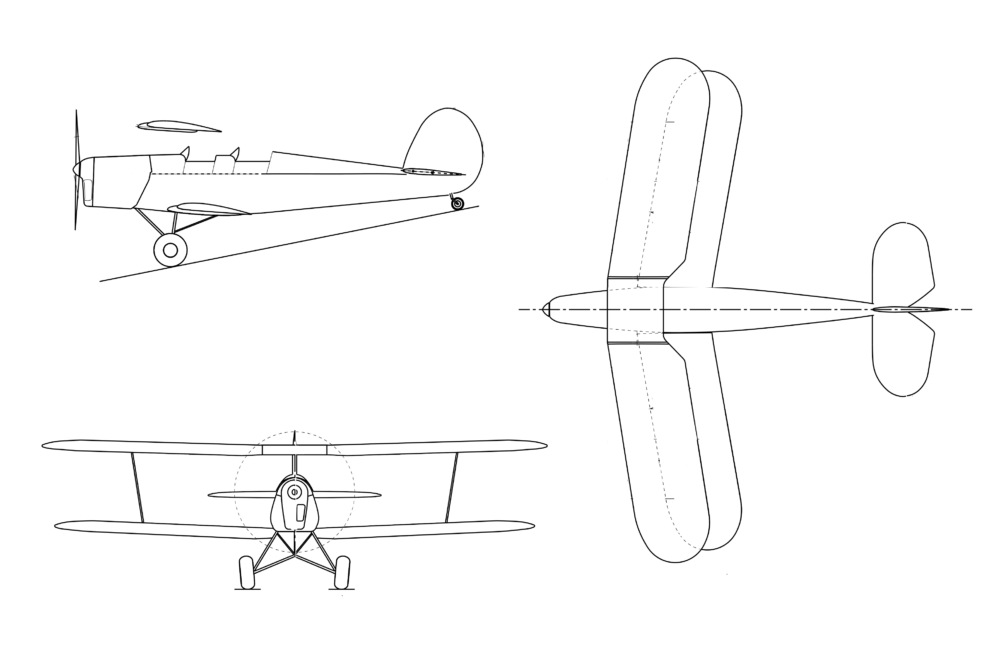

Modern microlight, retro charm

In the current range of available retro-look microlights, the SV4-RS is positioned between the Bücker and Funk Jungmann and the Kiebitz. It isn’t so close to the original as Peter Funk’s FK131, who would consider no other engine than the Mikron and, of course, who retained a steel-tube fuselage frame. But nor is it that far away from traditional retro-look biplanes, as is the Kiebitz. Irrespective of that, the microlight Stampe differs from the successful Platzer design in that you can buy it as a finished aeroplane.

As with the Kiebitz, homebuilders can buy both plans and individual components, but the microlight SV4-RS is also available in kit form. There are three levels of pre-fabricated kits available from Ultralight Concept, ranging from a complete flat-pack of materials (build time estimate 650-1,000hr) to an ultra quick-build with pre-covered fuselage and ready-to-cover wings (200-300hr). Customers can also attend assembly workshop courses, during which they can complete the airframe with the assistance of the company. Correct assembly is guaranteed because Ultralight Concept provides the jigs, which again reduces the costs for the homebuilder. Then there’s the ready-to-fly option, if your country’s regulations allow…

In France and Germany the Stampe has an image which is much the same as that of the Jungmann in Germany, the Tiger Moth in the UK and the Stearman in the USA. However, the SV-4-RS has all the advantages of a modern microlight, such as its Rotax 912 and a ballistic recovery parachute system. It’s an iconic biplane recreated for everyday use, as long as open-cockpit is your thing, and I think that deserves a round of applause.