Bardufoss – Alta. Distance: 165nm High winds were forecast at altitude, which presented a real problem as we were surrounded by mountains. Consider a 20kt wind at altitude, deflected downwards at an angle of 20° – this implies a vertical speed of around 700ft/min which is close to the maximum rate of climb for our fully laden Cherokee! Turbulence, updraughts and downdraughts can have a significant impact on a light aircraft like ours, not to mention that I was inexperienced in mountain flying…

Simply waiting until the weather was suitable to stick to our plan was out of the question. The weather would clear by the weekend, but by then Hammerfest would only be open between 1245 and 1500L – clearly not suitable for a midnight flight.

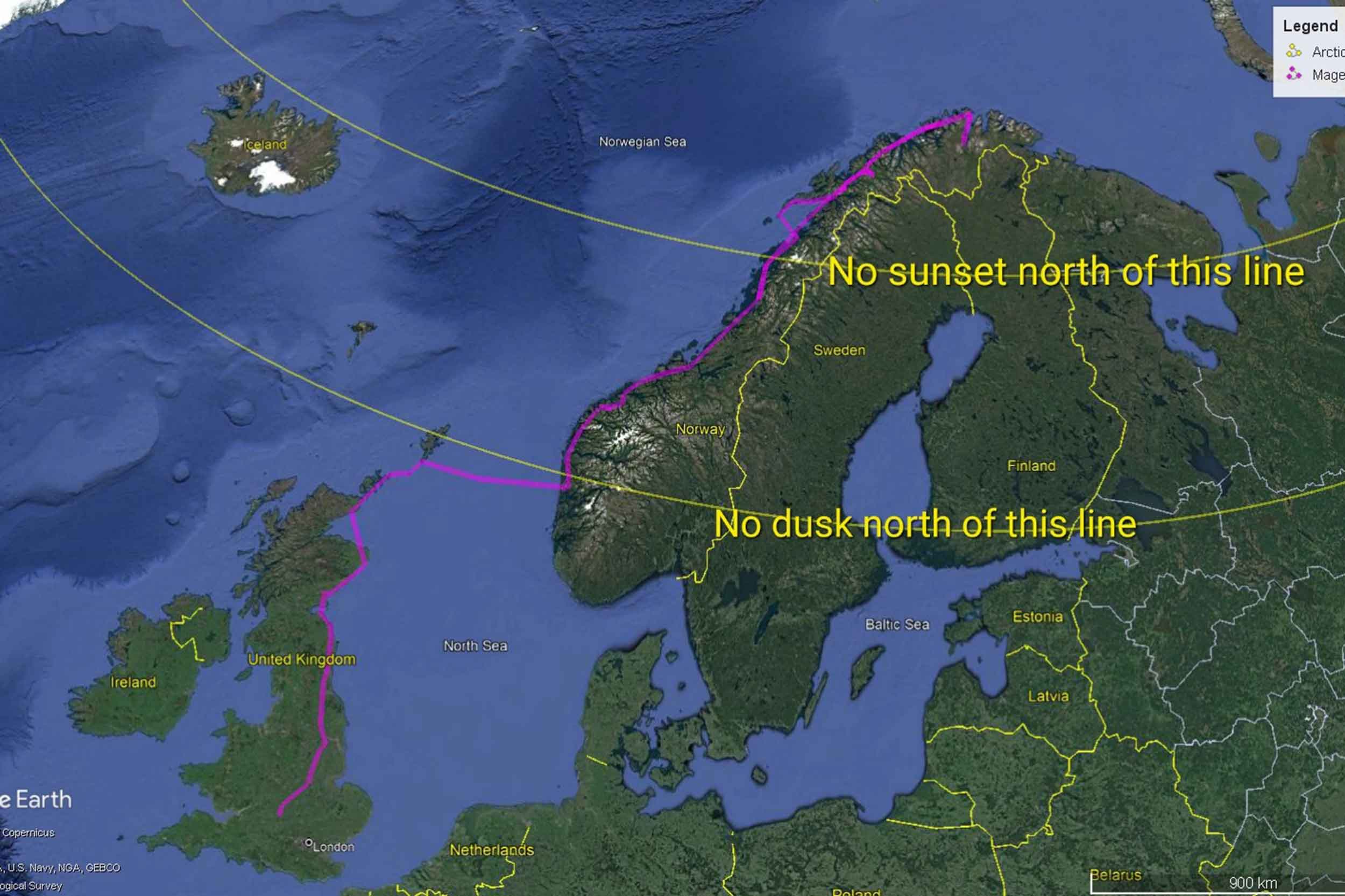

Our objectives were to fly at local midnight and to fly round the North Cape. The constraints were limited fuel availability, limited opening hours, and of course the weather. We spent hours plotting possible routes through the mountains on paper charts, always wary of the wind. We also needed options if there was an engine failure – there aren’t many fields in that part of the world, so ditching was always preferable to a forced landing on jagged rocks. There was only one solution, a late flight to Alta to refuel, then an even later flight around the North Cape all timed so that we could land at Hammerfest after midnight.

The flight out of Bardufoss and past Tromsø was, to quote Martina, ‘bumpy as hell’. But we did everything right to avoid downdraughts and to fly when the wind had abated. This was helped by there being windshear forecasts for many airfields, as well as wind speed data from anemometers on mountain tops near the airfields.

The timing of the next flight was critical…

Alta – Hammerfest (via the North Cape). Distance: 209nm

We took off at 2204 local time into bright sunshine. Flying along Porsangerfjorden towards the North Cape felt remote; big cliffs, lots of sea, late at ‘night’, with dramatic lighting thanks to the low sun peeking through gaps in the dark clouds. Once we got to the North Cape I was surprised to see lots of tourists and camper vans near the globe monument atop the 1,000ft cliff. Everyone had gathered to see the midnight sun. Hopefully they were equally surprised to see a little Cherokee bumbling past!

Our flight was made more spectacular when we spotted several pods of humpback whales lunge feeding in the calm waters below. To this point, the flight had gone to plan, and we were scheduled to arrive at Hammerfest at about 0025L. With Runway 22 in use and our approach being from the north-east, the AFIS anticipated me making a straight in approach. At the time, I was not visual with the field, and I felt that I wouldn’t be until quite late, given the surrounding rocky hills. I opted to fly anti-clockwise around the 1,250ft headland and join downwind left-hand instead to give me a chance to get acquainted with the aerodrome.

Unfortunately, the high ground at the end of the downwind leg made me fly higher (it’s surprisingly unnerving being close to rocks at that point of the circuit when you aren’t used to it). On final, try as I might – full flaps, idle power, full side slip – I couldn’t get anywhere near the runway. The last of the commercial traffic departed. The airport was scheduled to close in a few minutes. Attempt two wasn’t much better – I had no desire to fly closer to the rocks, so I extended downwind. I did not commit to extending far enough, and the situation repeated itself. Another go-around. This time the AFIS queried my intentions. There were no other airfields open for hundreds of miles – and I noted the less than subtle hint that it was his home time. Next time round I extended downwind much further, and we landed safely in broad daylight at 0027L. Mission accomplished.

Next day, by pure chance, we realised one of our unofficial objectives. A close encounter of the wild reindeer kind! They were sitting in the sun munching on grass in a secluded part of the town centre. Better still, just before midnight we saw them again from the hotel window, this time causing havoc: stopping traffic, drinking out of the fountain, destroying the flower beds.