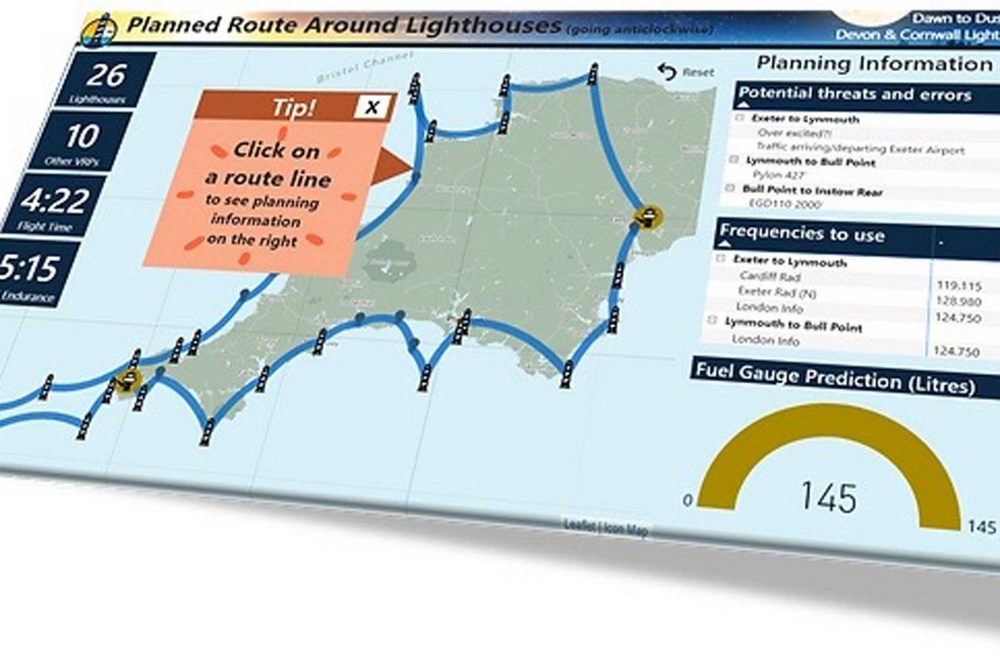

Two people getting into a DR400 and settling takes a few minutes, getting cameras stowed, Emergency Location Transmitter in place, PLOG ready, iPad set up, SkyEcho set and ATIS heard. We were ready to start and felt a little nervous and apprehensive.

Plan the flight and fly the plan… Hearing the tower steadied our nerves a bit. Then to the holding point and moment of clearance to take off. Brakes off, and the clock started.

The first leg was to Lynton Lighthouse. Enough time to settle down. DR400s are funny beasts, at least that’s the excuse best used. Once trimmed they fly on rails. Not quite trimmed, they climb and descend as they feel necessary!

We got G-LEOS trimmed and set up the cockpit for the flight. iPhones in pouches, PLOG handy. iPad and Sky Demon deployed.

We arrived over Lynmouth not long after departure and couldn’t see the lighthouse! Deep unease ensued. Reference to the half mill chart and SkyDemon showed it on a headland to the east of the town. Looking at the headland, no lighthouse… Deeper unease.

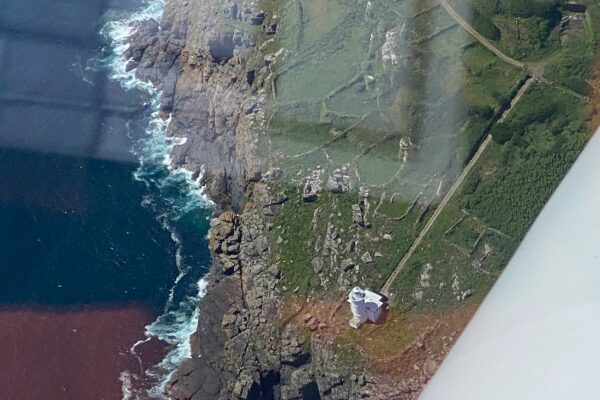

We flew on towards the headland and a tiny white tip of the light appeared, followed by the small complex of buildings and we had the first lighthouse in sight. Memorable for so many reasons.

We had found it! In our defence, it was not a huge tower, gaining its height for its beam from the location high up on the headland cliffs. All thoughts of 45° cones vanished and I overshot badly making a decent photo impossible. The second pass was much better. This could all come together, the plan could work.

The first lighthouse was ticked off on the PLOG and as we cleared the area and set off for the next lighthouse, we changed from Cardiff Listening Squawk to London Information.

Tracking along the north coast of Devon we passed the planned lighthouses one by one. Ilfracombe, then Bull Point where the keepers came out one morning to find huge cracks had appeared outside their door. The station was in danger of collapse into the sea! A new light was built and opened in 1974.