Tim gave me three bits of advice before I closed the canopy and started the Twister’s engine: Remember the tailwheel steering is geared, take off with one stage of flap, and enjoy the experience. At least I nailed two out of three…

Back in the late 1990s Matthais Streiker was enjoying considerable competition success with a radio controlled model aircraft. The story goes that the little aircraft handled really well, and after many friends suggested scaling it up to a full-size single seater, Matthias and elder brother Thomas did just that, creating the Silence Twister, which they went on to market as a kit.

The prototype flew with a Mid West Wankel Engine (maybe 50ish hp on a good day), but that was replaced by the Jabiru 2200, which is said by some to produce 85hp. Quite a few Twisters now fly with the ULPower UL260i which apparently delivers 107hp, albeit at 3,300rpm.

As well as producing an efficient aeroplane the Streiker brothers set about producing an efficient kit so, for example, there are only moulds for one wing and one tailplane (the wings have a symmetrical aerofoil). Obviously once built the wings aren’t interchangeable thanks to internal wing differences like the 40 litres per side fuel tanks. The original Twister had retractable gear, operated by a single electrically driven screw jack. The wheels didn’t fully retract and the mechanism added weight. All of which means that those Twisters that fly with fixed-gear are both lighter and faster than the retract version.

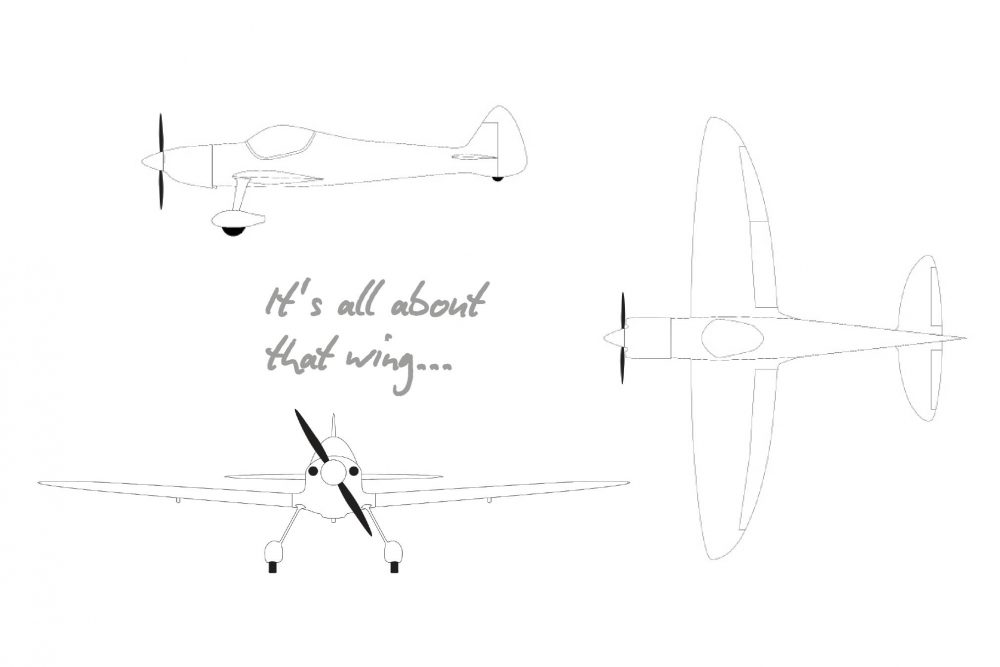

You can argue all day about which looks the best, but I’m going to sit on the fence and say that aesthetically they’re both cracking aeroplanes, thanks in no small part to that gorgeous and evocative elliptical wing. A couple of people have tried to explain that it wasn’t inspired by the Supermarine Spitfire, but I’m not buying that for one second!

The kit comes with all the structural elements built but not finished. The underside of the fuselage is covered by a large composite panel (also built but not finished), so you can get easy access to everything before finally bonding it on. I’m not qualified to judge the quality of a kit, but those who are tell me the Germans have done a very impressive job.

G-TWSS is one of two Twisters owned by Tim Dews. If the name’s familiar, it’s probably because Tim runs a two-ship Grob 109 display team with his son Tom, as well as heading up a glider repair and maintenance company – Airborne Composites – with another son Ben.