You don’t have to do a great deal of digging before you find someone online who’ll tell you that the Sling HW is set to be a modern day C182. Serendipitously, our carriage of choice for the journey from Wiltshire to Top Farm to fly the Sling was a 1977 C182Q. With a couple of thousand hours on what many call Cessna’s best single, I was very much looking forward to flying not only the Sling, but better still, the very aeroplane that I saw at Oshkosh after it was flown from the factory in South Africa to Oshkosh, after which it headed to Top Farm in Cambridgeshire, via Italy and Greece. Not your average set of cross-country flights!

My conclusion, if you can’t wait, is that the Sling HW is no C182, but it does have the makings of a damn fine aeroplane…

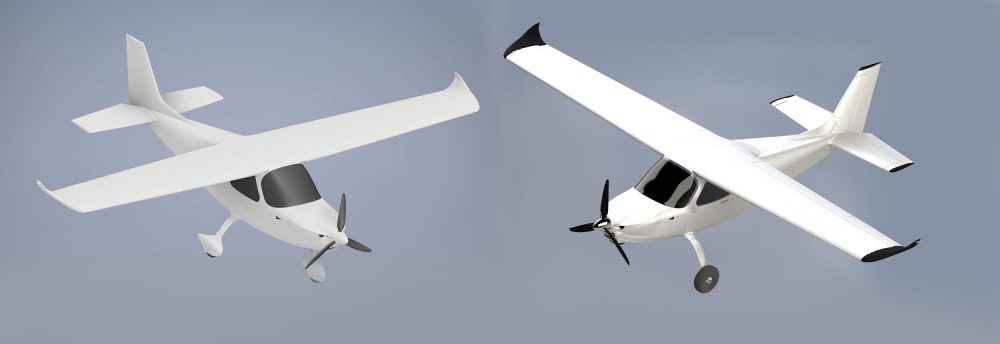

The Sling HW is the latest aeroplane to come out of the company behind the two-seat Sling 2 and the four-seat Sling TSi, both already approved in the UK by the LAA. The HW has a cantilever high-wing made from aluminium (pretty much the same wing as the Sling TSi), and a composite fuselage mated to an aluminium empennage. It’s powered by the turbocharged Rotax 915iS driving a three-blade electrically controlled constant speed propeller. There’s a spacious four-seat cabin, a large baggage area and, depending on your choice of avionics and extras, something like 450kg of useful load. The standard leading edge fuel tanks carry 99 litres per side with a couple in each tank being unusable. That means you can fill the tanks, have enough fuel for a good six hours, and still have a little north of 300kg left for people and baggage. Not too shabby at all.

Although this is not a feature pitching the Sling against the Cessna, some comparisons are begging to be made. The Sling has less wing than the Cessna, a large (but plain) flap, a lower max all up weight and that impressive useful load. It’s a bit smaller inside than the C182 (but still plenty big enough), and with its fold flat seats there’s an argument that the HW’s space is even more flexible, or at least configurable in a hurry. You could make yourself a flat bed in a C182, but it would involve swearing and spanners.

We also need to talk about engines. The Sling is hauled into the sky by a Rotax 915iS. It’s a brilliant modern engine that delivers 141hp for five minutes, with a max continuous of 135hp. The C182 may have a lumbering heavy lump of a not very sophisticated Continental or Lycoming up front, but for all its dinosaur DNA, that lump delivers a very useful 230hp – 63% more than the Rotax in an aeroplane that has a MAUW that’s just 28% heavier than the Sling.