Derick says: “More right rudder. More, more, you have to counteract yaw.”

I’ll need to get used to that.

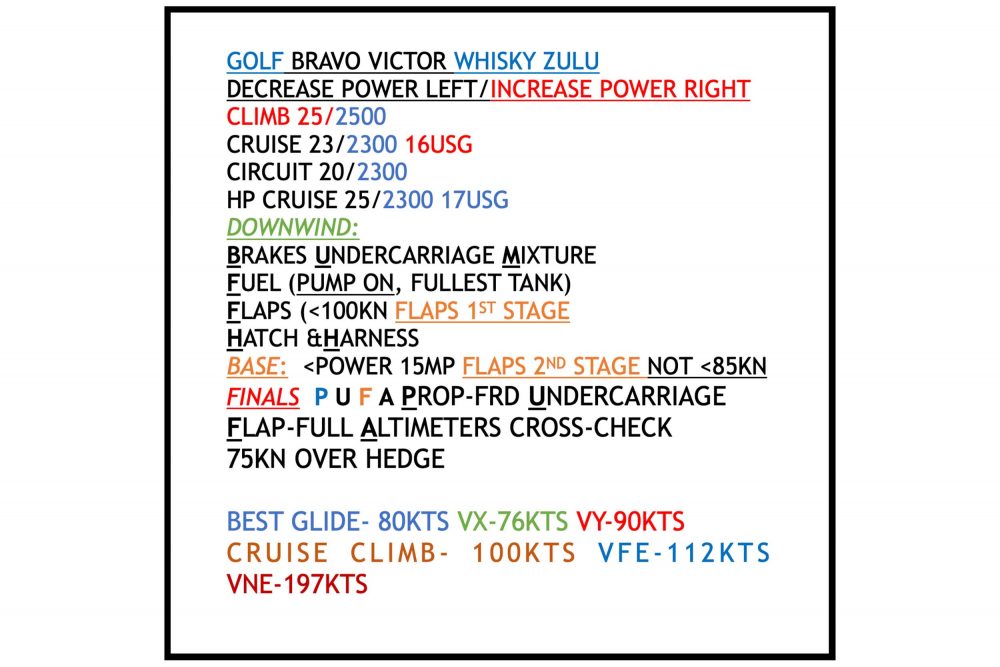

“Now you can reduce to climb power.”

Reduce? Not used to that either.

“A reduction in power is from the left, so reduce the power to 25 inches.”

I move the throttle until 25 inches shows on the gauge.

“Watch out for lag, the needle is still dropping.”

I compensate, now I’m flying too slowly and the balance ball is showing me I need yet more right rudder.

“The prop is already at 2,500rpm so just leave it there. Watch the manifold pressure, you’ll need an extra inch for every 1,000ft of altitude. Climb to 2,000ft.”

The manifold pressure has dropped again, I need to add more, oops I’m at 1,700ft already, lower the nose, don’t let her climb past 2,000ft.

“It’s very easy to overshoot your assigned altitude in this aircraft, you have to be ready for it. Get back on heading.”

I’m 20° off course! So much to think about.

“OK, now we need to set cruise power, which will be 23 inches and 2,300rpm. Remember a reduction is from the left so reduce the throttle first.”

Throttle to 23, then prop lever to 2,300… prop very sensitive… I’d forgotten about the lag on the throttle, it’s dropped to 18, I move it back to 23.

“Now reduce the mixture, watch the fuel flow gauge. We are burning 25 gallons an hour. We usually fill this aeroplane no more than 70 gallons for weight and balance. Reduce to 15 gallons an hour.”